Spotted beebalm: A native you need in your garden

Spotted bee balm is a fascinating native plant that will be a mainstay in our natural woodland garden.

Showstopper native is a pollinator magnet

Spotted beebalm (Monarda punctata) looks more like a plant belonging in some exotic locale rather than a native that is at home both in the hot sun of eastern United States as it is in the gardens and meadows of southern Canada stretching well up into northern Quebec and Ontario.

This native plant’s showiness, unique colour patterns and vigour makes it a perfect addition to any natural garden and a showstopper in even the most meticulous garden landscapes.

You could be excused for thinking this strange plant was a member of the orchid family. Its unique look, with several whorled flowers creeping up the stalk with small, tubular yellow florets painted with red spots surrounding pink-lavender leaf bracts that rise up the stalk in groups of three and more add a showiness that is truly a showstopper. The individual flowers are tubular, similar to the more traditional monarda flowers. They start off cream coloured but turn yellow with distinctive red and purple spots.

Spotted beebalm is a member of the mint family, grows two to three feet tall in optimum conditions and blooms in late summer to late fall. Its lovely minty fragrance fills the air around the plant especially if the leaves are bruised.

For those who enjoy using their plants for medicinal purposes, the leaves can used to make a natural herbal tea that is Said to cure all sorts of ills.

All that aside, it just looks cool with its flowers blooming right up the stalk rather than just at the end of the stalk like the more traditional beebalms.

Here you can see how the flowers grow up the stalks giving this beebalm a very different look than the others.

Spotted beebalm – also called horse mint – is unlikely to be a perennial performer in every garden but, once established, it can become a steady performer with little effort except regular reseeding. It can spread its own seed but a little judicial spreading by the gardener never hurts and should ensure a never-ending supply of this remarkable native plant in your garden

Although I did plant a spotted beebalm plug a few years ago, it never actually took so this is the first year I’ve had these in the garden.

From my research, it’s not unusual for the spotted bee balm to last only one or two years up to about four years in the garden. When it’s growing in a favourable location you can expect the plants to reseed often below or around the original plant or even in different parts of the garden.

A native plant for pollinators

In her incredibly informative and encyclopedic native garden book, A Garden for The Rusty-Patched Bumblebee, Creating Habitat for Native Pollinators, author Lorraine Johnson: writes: “Less frequently seen in gardens than the related Monarda didyma and Monarda fistulas, this plant should definitely be more popular. The flower clusters, in tiered whorls up the central stem, are very unusual – it’s not a stretch to compare them to the look of small pineapples. The overall effect of this Carolinian perennial is that it glows with a silvery sheen from the prominent silvery bracts.”

Lorraine recommends growing it with yellow wild indigo, flowering spurge and wild blue lupine.

For more on Johnson’s informative book on native plant gardening: A Garden for the Rusty-Patched Bumblebee , check out my earlier post here. Her earlier book, Grow Wild, is also worth exploring. click on this link for my post on Grow Wild.

Many gardeners will spread the seeds about the garden to ensure flowers return year after year. Others treat the plants more or less as annuals until they can get established in the garden.

The beauty of this outstanding native plant lends itself to a more creative approach to photography. For more on how I created this image and others featured in this article, scroll to the end of this post.

In our garden, I have planted four plugs which have all done well in this hot, dry summer. Some have certainly performed better than others. Our sandy, fast-draining soil is ideal for the plants, but I have found that they really prefer a lot of sun to perform at their best.

Locate them in a sunny spot with average to poor sandy or well-draining soil, do not overwater them and you are probably good to go.

Wildlife value in the garden

Being native to zones 3-9, the question will be asked: Are these plants beneficial to birds, bees and other insects in the garden?

It is actually a host plant for several moth caterpillars including the Gray Marvel Moth (Anterastria teratophora), Snout Moths (Pyrausta generosa, Pyrausta signatalis), Orange Mint Moth (Pyrausta orphisalis), and Hermit Sphinx Moth (Lintneria eremitus).

Spotted beebalm is also an important nectar source for various pollinators, such as butterflies, native bees, including bumble bees, wasps (large black and paper) and hummingbirds.

Like the other beebalms, it is resistant to both deer and rabbits. And, like other bee balms, they are susceptible to powdery mildew in the fall.

In my zone 6 the plants will start blooming in mid August and bloom for about three months through October and even into November. Later in the season they can provide an important source of nectar for migrating hummingbirds and butterflies.

Identifying the plants can be tricky in spring but look for lance-shaped, 3-inch by 1-inch leaves that are paired along the stalk and have serrated edges.

The root of the spotted beebalm is a short tap root surrounded by other fibrous roots, but unlike other bee balms, the spotted bee balm does not spread by rhizome making it a much better behaved member of the family.

They are very easy to grow from seed. Quick to germinate in spring in the garden or in a greenhouse. Simply sow the tiny seeds on the ground or in pots after last frost. You can spread them on the soil, press them in gently and put them in an area that gets morning sun and afternoon shade. Keep them lightly misted and germination should happen within two to three weeks.

It’s also easy to save seeds for next year’s gardening season. About three to four weeks after bloom, get a paper bag and carefully cut the stalk below the bloom. Careful you don’t turn the seed pod over or the small seeds will fall out. Dry the seeds in the paper bag. Seeds can be stored for about a year.

Because it is a short-lived perennial, you can usually expect your spotted beebalm to bloom in the first year.

More tips for growing the spotted beebalm

Over watering can cause powdery mildew and root rot.

One of only a few plants that can grow near black walnut trees.

The best way to get this plant is to plant it from seed, but it can be found in specialized native plant stores and on-line sellers. I purchased mine from Ontario Native Plants.

I have staked one of my plants just to keep it upright, while my other plants are growing naturally in a more meadow setting around other plants.

How I photographed spotted beebalm

Spotted beebalm is such an unusual plant that I wanted to photograph it using a variety of approaches, showing the plant in its natural environment as well as close-up images showing its detailed unique charcteristics from the tiny hairs on its tubular spotted flowers to the subtle beauty of its pinkish-lavender bracts.

Finally, its lovely flowers prompted me to get out the Lensbaby composer lens to take a more creative approach to documenting the plant.

In the first image: I used a combination of Lightroom and Luminar Neo post processing software to capture what may appear to be a simple close-up shot of a single flower/bract combination. The image is actually a composite of 3 images stacked together in Luminar Neo to substantially increase the zone of focus.

By focusing on three different areas of the flower from front to back, and combining them in Luminar Neo’s excellent stacking module, I was able to get most of the important parts of the entire flower in focus. This is a combination of only three images. If I wanted to have more of the flower in focus, I could have shot 10-20 images and merged them together, but I like to maintain some softness to keep the plant looking real rather than a more scientific rendering where the entire plant is in focus.

The second image: Here is a more straight forward approach to capturing the plant showing how the flowers rise up through the stalk. I needed to use a small aperture setting to capture both flowers in relative focus, so I used a feature in Lightroom to create a more blurred background to help the flowers better stand out from the background.

The final image: In this image I employed a number of tools to create a more softened ethereal look. First, I used a Lensbaby composer to create the original image. For those unaware of the Lensbaby line of lenses, they are designed to give the photographer control of the softness of an image to create ethereal, more romanticized and creative images that work particularly well with flowers.

Lensbaby lenses can be tricky to use because of their lack of sharpness and more experimental approach to photography. Using the manual focus soft-focus lens makes getting in-focus images difficult from viewing the back LED of modern digital cameras. However by adding a Hoodman photo accessory, which I have done, It is possible to get a magnified image of the back of the camera making focussing much easier. Quite frankly, I highly recommend the Hoodman for any photographer who uses the back LED on their cameras.

Once I was able to isolate the image that was sharp where it needed to be, I brought it into Photoshop where I added the soft veil of colour around the flower by picking out colours in the original image and then painting those colours into the photograph around the flower using a number of different brushes from a soft-bristle to a more textured style of paint brush.

Once satisfied with the image, it was imported back into Lightroom for final edits.

• If you are interested in exploring post processing further and are looking for a simple but highly powerful program to get you started, consider purchasing Luminar Neo. It is an outstanding post processing program that is capable of creating outstanding images. If you use my code “fernsfeathers” at checkout to get an additional 10 per cent off an already low price.

How to create a natural log planter

Adding a path-side planter from a large branch or decaying tree trunk is a project everyone can accomplish by following the steps in this post.

A natural log planter with the beginnings of native plantings including a maidenhair fern. The natural curve creates a shady spot for toads, salamanders and other critters. It is important to dig in both ends of the log so that it does not look like it is sitting on top of the soil.

From woodland vignette to garden feature

Part four of a series

One of the best additions we can make to our woodland/wildlife gardens is a simple rotting log, surrounded by native wildflowers and moss.

Not unlike a forest, where large branches and entire trees are left to slowly decay on the ground, our gardens benefit from the same rotting logs on our forest floors. These logs can quickly become home to any number of small woodland creatures, many of which are often unseen unless we really go looking for them.

A trillium pokes through the undergrowth from a dead tree stump creating a lovely woodland vignette that can be easily copied in our own woodland gardens.

During my Walks in the Wood, I have been drawn to woodland vignettes – like the one pictured above – surrounding downed tree branches or old tree stumps that have attracted a host of native plants and mosses. Recreating these scenes in my own garden has been a real joy, although I still have much to do before I can say they are completed.

The images above and below represent the beginnings of a project that involves a total of six natural woodland pathway planters.

If it’s large enough, you should see toads, snakes, even salamanders move in to the log along with a myriad of insects and fungi that all work in unison to break down the wood and add nutrients back to the garden.

Moss and a pink wildflower add a nice touch to our woodside planter.

The process of decay is slow and might even go more or less unnoticed, if it wasn’t for the birds and animals that visit the log looking for a quick meal or a place to escape predators. Photographers looking to improve their wildlife opportunities can use the log as a to capture wildlife in a natural setting like the image of the chipmunk farther down the page.

Ideally, we are looking to create a log planter similar to the artistic interpretation below.

Don’t remove those large branches after tree trimming

One of the best decisions I made several years ago was to tell our local tree service company not to cart off the large branches they took down from our upper canopy trees and, instead, leave them be on the ground.

One area where a lot of branches fell was our massive garden of ferns (link to fern garden post). It was the perfect place to just leave the large branches on the ground to break down naturally.

Our massive ferns grow up through the large branches and hide them throughout the summer months. During the early spring and fall and winter, I get to monitor the slow breakdown of the large branches spread over the ground.

“An interesting log or gnarly branch can add a very artistic touch to a shade garden or a final bit of realism to a woodland garden.”

In another area of the garden, I used the large branches that were removed from the tree to create a natural woodpile to provide shelter and habitat for the backyard critters that need places like this to escape predators. I’m sure some of them use it as shelter throughout the winter.

In fall, I throw on a layer or two of fallen leaves to provide even more shelter and create an even better environment for the large branches to break down over time.

If you are able to find a stump or old log with a hole in it, you just might have the perfect outdoor studio for capturing images like this. A few sunflowers dropped in the natural cavity will bring chipmunks and birds to your planter for some great photographic opportunities.

Five tips to find deadwood

If you do not have dead trees or stumps on your property to attract wildlife, you can always go out on a scouting trip to find a handsome trunk or large branch to place artistically in your landscape. Here are a few places to look for deadwood to create your planter.

If there is a natural woods nearby; ask permission to collect a few good-size pieces of deadwood. It’s best to collect soon after a storm blows down the branches, before wildlife have a chance to move in.

Call a nearby tree service company. They are usually willing to let you have anything you can haul off, or you may be able to arrange delivery for a small fee.

Check with your local cable, electric or telephone company. Trimming branches and clearing trees are routine maintenance and they are more than likely happy to let you take them.

Your local parks department and the town or city road crew may be able to help as well. They maintain public trees and are often looking to get rid of large branches.

Keep an eye out for possibilities in your neighbourhood. Your neighbours will probably be pleased to let you cart off their stumps an larger branches. Explain to your neighbours why you want them and how you will be using them. It’s a good way to raise awareness about the value of deadwood.

Deadwood does not have to be left on the ground.

In her book, Natural Landscaping, Gardening with Nature to Create a Backyard Paradise, Sally Roth dedicates several pages to the benefits of using deadwood in the woodland garden.

It is almost as useful standing up as it is lying down, she explains. An interesting log or gnarly branch can add a very artistic touch to a shade garden or a final bit of realism to a woodland garden.

If you have a large, long branch that is manageable, consider creating your own “snag” by simply digging a deep hole and planting the deadwood vertically.

I have a 8- to 9-foot branch planted in the back of our yard near my outdoor photo setup that is a regular stop for woodpeckers, nuthatches, red squirrels and chipmunks.

These are particularly prized by woodpeckers, and they make an excellent foundation for a feeding area. I have drilled holes in the branch where I insert bark butter regularly. You can also wire suet to them or hang a feeder. The dead tree is also the perfect landing spot for birds approaching the feeding station. Keep it far enough away that squirrels can’t leap over to the feeders.

Create a simple log planter

Letting nature slowly break down the logs is certainly one way to help wildlife, but using the logs to create a path-side planter is an even better one.

How often have you been out for a walk and saw the local arbourist either cutting down or trimming up a large tree in the neighbourhood. That’s a great opportunity to ask if they would drop off a large branch or two at your home. If you have access to a truck, you could obviously just throw it in the back and take it home on your own.

Some of the tools I used to hollow out a part of the log to pack it with moss and/or wildflowers. A battery-operated chainsaw is an excellent way to cut the initial grooves, which can then be chiseled out to your liking.

Once you have it home, you can go to work carving out a portion of the log where you can pack in a rich forest soil loaded with compost, rotting leaves and bits of fungi that will quickly go to work breaking down the wood.

If you are comfortable using a chainsaw, you can create a large hollow in the log in no time. If a chainsaw is not something you want to get involved with, you can create the planter with simple tools like a hammer and chisel.

To speed up the process, consider using a power drill to first create holes in the area you want to hollow out. Once the holes have been drilled 5-6 inches deep, you can begin chiselling out the wood. Depending on the size of the log, you may have to drill and chisel out the wood a few times before you have the look and depth you want.

If it’s possible, use a longer drill bit to create drainage holes through the log. Drainage holes may not be necessary since the idea behind the project is to create a rotting log, and the wood in the log will absorb a lot of the moisture anyway, but drainage holes might be appropriate depending on what you are planning to grow in the fallen-log planter.

I have seen many of these natural planters with colourful bedding plants filling them up. That’s fine if you are looking to “pretty-up” a corner of the yard, but using native or at least woodland-style plants in and around a natural planter looks and feels much more appropriate.

Think wildflowers like hepatica, trilliums, maidenhair ferns, mushrooms and small succulents. A natural path-side planter where you can control factors like soil PH, is the perfect place to grow Bunchberry (cornus canadensis) or other acid-loving plants.

Three native foam flowers and a Columbine are added to the back of the planter that can be seen from our patio.

In his book, Landscape with Nature, Using Natural Design to Plan Your Garden, Jeff Cox writes that “you can make a totally natural planter by hollowing out the centre 1 foot deep.” He suggests planting the old log planter with ferns, begonias, impatiens, or hens-and-chicks, but I prefer a more natural approach using native wild flowers including trilliums, dog-tooth violets and even wild ginger along with hepatica and spring beauty. It might also be the perfect spot to try some native orchids.

A log planter can also be a great place to grow a small bonsai-like shrub – suggesting the rebirth from a dead tree into new life. Again, try using a native shrub like a serviceberry, or one of the many small-shrubby native dogwoods, and viburnums preferably one with berries.

Commercial alternatives to a natural log planter

If carving up an old wooden log with a chainsaw or painstakingly chiselling one out is too much, there are much simpler ways to achieve the overall look without lifting a finger.

Commercial stumps are available that give you the look of an old, hollowed out tree stump without the work and the eventual complete break-down. High quality concrete planters can look remarkably real.

This example of an old wooden log planter from Wayfair.com is a good indication of what is available.

The concrete containers that are made to look like a real tree trunk are perfect for the woodland garden. You can purchase ones that stand up more or less vertically to give height, or planters that are more like fallen logs that lie on the ground horizontally.

These have the added benefit of being able to be easily moved around the garden.

Of course, you will lose out on many of the insects and small animals that would readily move into the more natural pathside planter, but you will be gaining a woodland aesthetic that will surely bring a smile every time you pass it by.

Native plants on the woodland walk

I take a walk in the woods to explore the native wildflowers. Trilliums, Marsh Marigolds, Wild Geraniums, Mayapples, Forget-me-nots and a host of others that we can use in our own woodland gardens.

“May your life be like a wildflower, growing freely in the beauty and joy of each day.”

Trilliums, cranesbill, violets and Redbuds: Rooted in the woodlands

Part Two of the series

Most people enjoy a walk in the woodland. They marvel at the discovery of a favourite wildflower, shrub or flowering tree growing deep in the forest.

In many places around the world, those same plants growing in a front garden become the talk of the neighbourhood, often bringing HOA administrators or city inspectors to tell the homeowners to cut these same plants down, or worse, rip them out and replace them with tidy non-native plants that they all know and love.

Is it the plants that are the problem, or where they are growing? should it even matter?

Wild violets early bloomers

Yes, the same violets that neighbours work so hard to keep out of their barren yards of turf grass are among the first blooming native woodland wildflowers.

Without getting into an in-depty discussion of why we need more native plants in our gardens – front and back – I am a firm believer that where and how native plants grow make a world of difference to how they are perceived.

In the woodland and other natural areas, Mother Nature does the planting. Somehow, she seems to know how and where to grow these plants so that they fit in perfectly in most cases and make us stop in our tracks and marvel at their perfection.

Click on the links for my earlier post entitled “A Walk in the Woods” and the accompanying Photo Gallery.

Mayapple in Bloom

Most passersby will never notice the lovely white flower beneath the large, attractive leaves of the Mayapples that spread across the woodland floor, but if you lift one of the leaves you just might see the large white flowers that eventually become the “apple” later in summer. The seeds of the “apple” seed pods are eventually planted by ants and other fauna.

She doesn’t worry about planting in ones, threes or fives. Odd numbers are not in her vocabulary. She plants as many as needed, where they grow best. The fact their placement almost always feels right might be coincidence, or meticulous planning, but we all know it’s really about what comes natural and what really works in that world.

During my walks in the woods, I couldn’t help but notice the familiar and unfamiliar plants that emerged with the coming of spring.

Now, I am no expert on native plants, nor do I believe that there is only room for natives in a garden setting. We definitely need more natives in are gardens, but there are aesthetic and other legitimate reasons for adding non-natives to our garden beds.

In the forest, however, non-natives become more controversial, especially those plants that leave our gardens and spread aggressively into the forest. Buckthorn, wild garlic and purple loosestrife are just three non-native species that threaten our woodlands in Northeastern United States and Southwestern Ontario. There are too many more to list – Lilly of the valley and ditch Lillies (those ubiquitous orange day Lillies that seem to have place in every garden) just to name a few.

Our woodland native plants need protection, but in the meantime, we can enjoy them in their natural environments provided we know when and where to look. Once we find them, we can take note of how and where they are happily growing, and ask ourselves why they are growing so successfully in that particular part of the forest or woodland clearing.

click on the link for my earlier post on why we need to plant more natives in our gardens.

By asking ourselves that question, we can locate them in our own gardens with greater success.

Lesson 1: Mother Nature never plants trilliums where she thinks they will look best or seen by the majority of visitors to the woodland. Instead, they appear where they will grow best – in the right light, in deep, rich forest soil formed over years of leaves falling to the ground and decaying year after year. They are not growing in that sandy soil or heavy clay, many of us try to force our trilliums to grow in our gardens.

A cluster of Wake Robin trilliums photographed from above to show their nodding habit and the habitat where they grow. Notice the abundance of fallen leaves and native white pine needles.

What native Trilliums in the woodland can teach us

Trilliums are a great example of our spring ephemerals. They begin to emerge when the leaves have yet to fill the tree canopy. Without the leaves shading the ground, the sun’s rays reach down deep into the forest floor warming it quickly and giving a kick start to the winter-dormant plants.

By the time the leaves are emerging from the upper canopy, our trilliums are beginning to appear. First in sunnier west-facing areas that get sufficient morning and afternoon light, followed by other areas on the forest floor.

Click on the link for more on growing trilliums in our woodland gardens.

Mother Nature looks for ideal conditions and then lets the trilliums go to work building drifts and, at times, massive carpets of Ontario’s official wildflower.

A wake robin nodding in their typical style of growth.

On my woodland walks this spring, I have watched the trilliums emerge in various parts of the forest, mostly in small groups rather than large drifts, and certainly not in any large carpets that I have witnessed elsewhere.

Along the way main pathway where hundreds of people walk, run and ride their bikes, the trilliums survive and put on a nice show. Some take up perfect spots overlooking the clear creek that runs alongside the path. These are particularly pretty with the stream flowing past them and make for potentially lovely photos.

But, it’s off the main path over the many surrounding hills where I find the largest number of trilliums and certainly the most photographically pleasing compositions. Here, they are more or less undisturbed. The leaf cover is deeper, the fallen trees are decaying more naturally without much interference from humans and the plants are able to spread their seed more efficiently.

On one recent walk along the main path, I noticed a much smaller path going almost straight up vertically. With my trusted, and highly recommended walking sticks, (Amazon Link) I climbed the steep hill, only to be greeted by a lovely woodland scene full of fallen tree stumps in various levels of decay, wood ferns and trilliums – most in small groups, but others growing singularly.

From my vantage point on the other side of the hill, I could hear people walking by (talking loudly of course even in the quiet of the woodland), but I was in another world entirely.

I imagined creating a similar “secret garden” in a quiet area in our woodland garden. It could never match this magical discovery, but maybe I could capture the spirit of the place.

Lesson 2: Look to capture special places you discover in the woodland in your own garden. You will likely never replicate the exact feeling, but you can capture the spirit of those places. A fallen log left to become moss-covered, a pocket of deep rich humusy soil where you can successfully grow trilliums and wood ferns. Add a natural seating area where you can escape the noisy world around you. Maybe add a natural stone basin to encourage wildlife to visit your secret place.

Woodland scene

How easy would it be to duplicate this first scene in your woodland garden? The cut tree is the result of the local conservation authority maintaining the forest to some degree after fallen trees block walking paths.

In another, much more distant area of the woodland, I come across a grouping of Wake Robin hidden in a quiet area far from the groups of walkers, families with children out for a stroll and bike riders ripping up the forest floor with their knobby tires.

I’m guessing these, more rare, grouping of maroon trilliums have escaped the eye of people who think the wildflowers are there for only their enjoyment and walk off with either an entire plant or just the flowers, hoping to get them home in time to pop them in a vase.

Or maybe, it’s just ideal conditions that brought them there.

As spring opened its arms to more and more wildlfowers, from the large drifts of Mayapple and skunk cabbage (covered in more depth in my first post A Walk in the Woods), the emergence of large drifts and smaller clumps of Forget-Me-Nots began lighting up the forest floor.

The blue mistiness of a blanket of Forget Me Nots surround a large tree just off the path in the woodland.

Forget Me Nots: Native or non-native?

A ray of sunshine catches a clump of Forget Me Nots along a main path. Being out late in the day allows us to capture special moments like these.

I was always of the understanding that Forget-me-nots were an introduced species that naturalized in our woodlands, but I have learned that, in fact, there is a species of native Forget-Me-Nots in the United States and Canada. That’s good news because they are certainly in abundance in the woodland around my home as well as in our garden.

The species native North America including Ontario, Canada is Myosotis Macrosperma, also known as the large-seed forget-me-not. It is in the borage family (Boraginaceae) and found in a variety of natural habitats, including areas of bottomland forests, mesic forests and prairies. Like most native woodland plans it likes nutrient-rich soils, but can be found growing in less than ideal soils including pastures and fallow fields.

Myosotis macrosperma is a spring blooming herbaceous annual that produces a cyme of white flowers. Myosotis macrosperma can be distinguished from the non-natives by its longer inflorescence nodes, larger and more deciduous calyx, and larger mericarps

While the common forget-me-not (Myosotis sylvatica) is not native to North America and is considered an invasive species, it has naturalized in various regions.

I admit a soft sot for these lovely little flowers and enjoy photographing them whether they are the native or non-native variety. They are not around for long and are certainly willing self-seeders.

Lesson 3: Unless you want to be inundated with an abundance of Forget-me-nots in your spring garden, think twice about introducing them to your garden. On the other hand, if you like the blue carpet of these early spring bloomers, feel free to let them spread through areas of the garden and experience the joy of the misty blue carpet every spring. In an area of our garden, the Forget-Me-Nots are happily spreading and allowed me to capture the image of the spring fawn (above).

Many of the images in this post and other posts from a “Walk in the Woods” were post processed with Luminar Neo software. If you are looking for an inexpensive, but comprehensive editing program for beginners, check out Luminar Neo’s wide ranging tools to take your editing to new heights. Check the bottom of page for a 10 per cent discount code.

A river of Marsh Marigolds is a stunning sight to come upon on a misty morning in early May. Below, a single bloom shows how beautiful they are in close up.

A river of of Marsh Marigold

I stumbled across a river of marsh-marigold (Caltha palustris) also known as kingcup one misty morning on a path a little out of the way of the main walking path, but certainly in an area regularly visited by the many who walk the conservation area trails.

A single marsh marigold bloom from the river that blanketed an area in an open, marshy area of the woodland.

I photographed the incredible scene from every angle I could imagine to ensure I could do it justice. In other areas, smaller clumps of the joyful sunny flowers graced the woodland wetlands.

Marsh Marigolds, is a small to medium sized herbaceous perennial and member of the buttercup family. As its name implies, they are native to marshes, fens, ditches and wet woodlands throughout the northern hemisphere. These lovely plants flower between April and August depending on location. For more details, use this link to read Wikipedia’s extensive description.

Wikipedia includes this description of the flowers or (inflorescence): “The common marsh-marigold mostly has several flowering stems of up to 80 cm (31 in) long, carrying mostly several seated leaflike stipules, although lower ones may be on a short petiole; and between four and six (but occasionally as few as one or as many as 25) flowers. The flowers are approximately 4 cm (1+1⁄2 in) but range between 2–5.5 cm (3⁄4–2+1⁄4 in) in diameter.”

How is that for a mouthful?

Lesson 4: All I know is that these native wildflowers thrive in the local wetlands. Unfortunately, I don’t have a natural or man-made pond in our garden, but if I did, these would be a must-have. Not only do they light up the area with an abundance of golden flowers, they provide pollinators with an early-spring source of food. A win-win for our gardens.

Wild geranium or cranesbill

A wild geranium shows off its lovely mauve flower. These are an important early source of nectar and pollen for a host of insects.

Wild Geranium making their presence felt

Most woodland gardeners have at least one wild geranium (cranesbill) in their gardens. Whether it’s the native plant or one of the many “nativars” that have invaded most nurseries, these hardy, low-growing ground covers work as well in the natural woodlands as they do in our gardens.

Click on the link for my full story on using wild geraniums as a ground cover.

As I write this post in late May, the Wild Geranium are just starting to flower both in the natural woodland and in our garden. The mauve flowers are always a welcoming sight growing among the ferns and adding colour to the forest floor. Check out my earlier post on growing wild geranium as a ground cover in the woodland garden.

As May turns to June and the woodland matures from spring to early summer wildflowers, ferns, mayapple, sedges, Jack-in-the-pulpits and other primarily foliage plants begin to take over from the ephemerals in the woodland, where they go about their business of shading the forest floor.

I’ll keep visiting my woodland, exploring and discovering more native flowers, plants, shrubs and trees as spring turns to summer. Here are just a few more I came across during my Walks in the woodland.

Jack in the Pulpit

Areas of the woodland support numerous Jack in the Pulpits, which easily go unnoticed on the greening forest floor..

A native Redbud tree has found its roots in a dense part of the woodland along a stream.

A serviceberry tree enjoys a ray of late evening sunshine that lights up it myriad spring flowers. In summer, the tree will be visited by woodland birds and mammals looking to get a taste of its sweet red fruit.

Concluding thoughts on a walk in the woods

Walking in my local woodlands this spring and exploring the flora and fauna that grows naturally there has been an eye-opening experience. Not only have I watched the forest come to life, but I have witnessed the change from week-to-week, day-to-day.

It’s been an inspiring couple of months as the regular visits allow me to become more intimate with the landscape, flora and fauna. Our woodland is actually part of the Hamilton Conservation Authority and is located primarily in a deep, rather hilly ravine.

In the past, a very bad hip would never have allowed me to hike the area, especially considering the extreme variations in topography. The only reason I am able to hike these woodlands as extensively as I have is with the use of Nordic hiking sticks. Whether you are young or old, in perfect health or struggling to keep up, Nordic hiking sticks should be an important part of your journey into the woods.

I have used hiking sticks for close to a year and would not be without them on any hike into the woods.

If you live near to a woodland – and most of us do – take time to experience it, explore it and discover the hidden treasures nature provides us if we make the effort.

• Many of the images in this post and my other “Walk in the Woods” articles, are processed with Luminar Neo photo editing software. If you are interested in taking your photographs to a higher level, you should consider exploring Luminar Leo. It’s an ideal software package for those who are new to photo editing. The photo editing software capitalizes on Ai features to make photo editing much simpler for the beginner.

For a completely different look at what Luminar can do with film that is digitized, Check out my review of the Pentax PZ20 and Luminar Neo processing here.

If you decide to purchase Luminar Neo, you can use the code “FernsFeathers” for a 10 per cent discount at checkout.

What about all those cultivars of Native Plants?

Should nativars be used in our gardens or is it better to stick with unmodified native plants?

Are “Nativars” safe to plant in our gardens?

"‘I love the cultivars or nativars of so many of our native plants. Are they okay to use in our natural garden?”

That’s a question many natural gardeners are asking these days as they try to do what’s best for the environment while at the same time being tempted by a “better” rendition of an already existing native plant.

A hummingbird visits native bee balm in our garden.

What is a nativar and how to spot them at the nursery

First of all, what is a “nativar” anyway? In their book A Garden for The Rusty-Patched Bumblebee, authors Lorraine Johnson and Sheila Colla offer this definition: “You can tell whether a plant is a cultivar because it is “named” in quotation marks.” They then go on to give an example of a named cultivar of the native plant Monard didyma which would be in nurseries with the tag Monad Didyma “Cambridge Scarlet.” This plant would be a cultivated version of the unmodified species plant. These native plants have been “deliberately selected, cross-bred or hybridized for traits that are considered desirable by the nursery trade and gardeners.”

In the image below, the term Nativar is on the flowers name tag and the flower has a name “Ruby Star”. True natives would only use the name Purple Coneflower and/or the botanical name Echinacea Purpurea.

These flower tags are clearly marked ‘Nativar’ in the lower right but the name of the plant “Ruby Star” is a giveaway that this is a hybrid of the native Purple Coneflower. The jury is still out on these plants, but when given the chance, it is always better to use the true native plant.

The authors go on to explain a further complexity gardeners face when trying to decide whether to add the plant to their garden “because some “named” plants for sale at nurseries are “varieties” rather than cultivars. Look for “var” in the name of the plant, which indicates that it is a variety, not a cultivar. Varieties are naturally occurring and are selected by nurseries for their desirable traits.”

Okay so are these “varieties” desirable for your garden, the environment and the wildlife that are dependant on native plants?

Native plants are always a good choice when deciding what to plant in your garden.

The answer to this question is yes. Johnson writes: “In terms of biodiversity, the important difference between varieties and cultivars is that with varieties, the traits can be passed down to the plant’s offspring via sexual reproduction, which leads to genetic diversity within the plants. With cultivars, the trait(s) is not passed down via sexual reproduction, which means that to retain the trait(s), the plant is cloned. Thus each cultivar is genetically identical to every cultivar of the same name, and cultivars do not contribute to genetic biodiversity.”

In other words, “They do not have the genetic variations that ensure resiliency in species and adaptability to stressors such as diseases, pests and climate change,” the authors write.

The authors go on to cite a study by Dr. Annie White at the University of Vermont which arrived at interesting results showing that although native plants performed better than native cultivars in most cases, cultivars were used by pollinators both as a source of nectar and pollen.

Other studies also show varying results.

Authors Johnson and Colla in their informative book A Garden for the rusty-Patched Bumblebee conclude that “in the absence of of empirical data it is prudent to plant unmodified native species. Unless the nativar has been evaluated in a comparative study, its pollinator value is simply assumed, rather than known.”

They conclude that by planting “unmodified native species, you not only contribute to helping pollinators but also to plant conservation, including genetic diversity.”

As readers can conclude, planting unmodified native plants is always the best choice for both the environment and our native wildlife, however, I think planting “nativars” and “varieties” are probably a better choice than planting non-native species, especially when they have the potential to force out native plants by taking over natural areas.

In time, future studies will reveal more information on the dangers and benefits of using these modified native plants and will help to definitely answer the question of whether we should be using these in our garden.

In the meantime, it’s best and safest to stick to native plants.

A Garden for the Rusty-Patched Bumblebee can be purchased at most local bookstores or at on-line stores like Amazon.ca or often used at smaller book sellers under the umbrella group Alibris.

Yellow lady slipper orchids in the garden

Growing hardy Yellow Ladyslippers can be difficult, but the rewards are well worth it.

Where to purchase hardy Yellow Lady Slippers and how to grow them in the garden

I’ve always had a thing about Lady Slipper orchids. In my earlier years, I spent a lot of time and effort driving all over the area searching out these elusive wild orchids in the forests and wetlands in the area.

Among my favourites were the delicate and truly lovely Yellow Lady slippers.

Some of my best photographic images, in fact, were taken in a nearby cedar bog where the yellow orchids (Cypripedium parviflorum) grew alongside showy ladyslippers. They bloomed in early June and my buddy and I could only stand a half hour or so in the cedar swamp before the mosquitoes and who knows what else ate us alive.

I have not been back to see if the wild orchids are still growing there, but I suspect they have been dug up by gardeners thinking they can grow them in their own yards. Or, maybe even worse, the bog has been drained in the name of progress.

Both are big mistakes, but I want to emphasize that digging these rare wild orchids is almost criminal. For more on why you should never dig wild plants, see my earlier post here.

Not only is it rare for these orchids to survive in a completely different environment than what they were growing in – a heavy cedared bog – many of these orchids need a fungi present in the soil to survive, or at least prosper.

The beauty of wild orchids

Growing hardy native orchids is possible but not for the faint of heart.

And don’t take my word for it. Frasers Thimble Farms, an expert orchid grower on Salt Springs Island on Vancouver Island in Canada states on their website this about growing any hardy Lady Slipper orchid: “The most beautiful of all the Hardy Ground Orchids are the Lady Slippers, however, they are not the easiest plants to grow. Frequently, people need several attempts before mastering their cultivation. In cultivation, many have success growing them in pure perlite or in pots with a mix of equal parts of peat, sand and perlite. In nature, they often grow in bogs, but they tend not to like soggy conditions. Until recently it was not known how to germinate the seed of these beauties, but a few people (labs) have worked out how to in sterile medium (including us now). … We will also have a small selection of mature single eyed divisions of garden grown plants (mature plants). We have also recently begun to sell large plants with two growth points ( double eyed Divisions).

In speaking to Richard Fraser this week via email, he reports that: Yes, in fact, “we grow lady slippers. A few species and a few hybrids. We have been shipping them in the Fall but we don’t ship in the spring anymore. We no longer sell young plants in culture ( still in the test tubes) as the mortality rate was too high. We sell 4-5-6-year-old plants that are near or at bloom size and a few 7-8-year-old plants that are a little larger. We no longer ship to the USA.

Okay, so they are available but at a cost. Expect to pay upward of $100 Cdn with shipping for a mature plant.

Frasers Thimble Farms only sells to Canadian purchasers. There are U.S.-based sellers who grow in labs that only sell to US-based buyers. One mail-order seller is Great Lakes Orchids who have a long history of lab-cultivated hardy orchids. Check on-line for more, if you are interested.

I am sure that an on-line search will also bring up European sellers as well.

How to grow hardy Lady Slipper Orchids

Great Lakes Orchids website has an outstanding comprehensive website page about how to grow a variety of specific hardy Lady slipper orchids. This information is critical for anyone who is thinking of trying their hand at growing these orchids. Go here to see their recommendations on growing orchids.

For example, on Yellow Lady Slippers they recommend the following:

“Existing on a variety of soil compositions, but generally requires a slightly acidic condition, PH 5.5 is typical. It can be found in openings in hardwood forests, androadside ditches, and grassy fields, but the common denominator is PH, PH=5.5

Enjoys full morning sun with high dappled shade in the hot afternoon. Tolerates moisture but sites should be well drained. Can be found on gradients and slopes that provide good drainage. Common name: Small Yellow Lady Slipper.

Recommended soil mix: MetroMix 560 SunCoir, amended PH to 5.5. CEC=medium

Fertilization: Enjoys regular feedings of ¼ strength fertilizer. We use water soluble fertilizer. Stop fertilizing when flowers open.

Water: Typical water supply, city, well, rain water, etc. Municipal chlorine and fluoride are not a problem in any way, they’re fine.

Fungus control: Use a systemic fungicide as per labeled directions

Overwintering: Protect dormant eyes and buds from mice, voles, and squirrels. Hardware cloth may be used; remove early in spring before they break dormancy in spring.”

East-coast seller to check out

In Canada, an East-coast seller that looks promising is Bunchberry Nurseries that is offering an impressive assortment of Lady Slippers. Jill Covill, owner of Bunchberry Nurseries says that her company does ship orchids to Canadian customers. Jill says customers should go to the website and e-mail her directly to order their favourite Lady Slippers.

Bunchberry Nurseries grow all their Lady Slippers from seed. Check out their website for more information.

My experiment growing hardy Lady Slipper Orchids

Back to my personal experience with these orchids. When I was photographing these orchids in the wild, I never thought I could grow the yellow Lady Slipper in my own garden.

Years later, I was surprised to find out I was able to purchase a Yellow lady slipper from a specialty nursery about an hour from my home. Unfortunately they are no longer in business.

The nursery took advantage of new cutivation methods of native Lady slippers. These Lady slippers orchids – like the orchids that are only recently readily available in every grocery store, nursery and many big box stores – are beginning to get a little more common in gardens as a result of the new scientific cultivation through root cuttings.

Without getting into specifics, cultivating and bringing these cold-hardy varieties remains a painstaking task, which helps explain their high cost.

If cultivating them was difficult, growing them successfully can be even more difficult, depending on a number of factors not the least of which is your garden’s soil, lighting conditions and planting locations.

While I’m saying that growing these orchids can be extremely difficult, I’m also aware that some people have enormous success growing these orchids in their garden. I think it’s a combination of the right soil, location and care, with a fair bit of knowledge and dedication.

I am certainly not an expert Lady slipper grower but have managed to keep the lady slipper alive for several years despite only getting a single bloom a few years back. My guess is that if I don’t do something soon to turn it around, I may end up losing the plant.

So, I’ve decided that this year is going to be the year of the rejuvenation of my Yellow Lady slipper. Once the plant emerges this spring, I plan to dig it up and replant it into a container where I can control the environment where it is growing, including soil, fertilization, sun and water.

I know a lot of readers are going to tell me that they have successfully grown wild orchids for years in their gardens, especially those in the maratimes where Moccasin flowers (Cypripedium acaule, also known as the pink lady's slipper) can grow like weeds in some areas, but here in southern Ontario and I’m guessing the American north east, growing wild orchids is hit and miss and more miss than hit.

Unlike the Moccasin flower, the Yellow Lady Slipper can be more easily grown in a garden setting.

My goal is to get our yellow Lady Slipper to a healthy stage where I can actually divide the clump and begin to enjoy more of these outstanding woodland plants.

If planted in a favourable location with good soil etc, these plants can prosper and form large clumps which can be divided and spread throughout the garden.

I’ll keep readers informed of my progress over the spring and summer.

Stay tuned for more on my Yellow Lady Slippers.

If you are looking for more information on Native Orchids, you might want to purchase Native Orchids of the Southern Appalachian Mountains. (Amazon Link) It’s available both in hard cover an in a kindle version and is considered an authoritative guide showcasing the diversity of the native orchids of the southern Appalachian mountains. The book covers the 52 species--including one discovered by the author and named after him –found in a region encompassing western Virginia and North Carolina and eastern West Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee.

If you would like to purchase the book from Alibris (an umbrella group of small book sellers in The US and Canada you can go press on this link. These book sellers often offer outstanding deals on used copies of the books and are highly recommended.

Wild Ginger: Native ground cover for your shade garden

Wild Ginger is a native ground cover that just might make a great replacement for your hosta plants.

Natural replacement for small hostas

This image of Wild Ginger shows off the native plant’s flower beautifully. The small reddish-maroon flower is normally difficult to see because it grows under the leaves and emerges for a short time in spring.

Canada Wild Ginger (Asarum canadense L.) has been described as an ideal replacement for hosta in the native garden, and I couldn’t be happier.

I mean, who isn’t up for a native plant to replace the ubiquitous hostas that have become a mainstay in every suburban garden? I know that I am ready for a change.

Don’t get me wrong, I love a beautiful hosta but so do deer, slugs and a host of other backyard wildlife.

What makes this low-growing ground cover so special is the fact the plants contain a type of acid that ensures deer, rabbits or any other hungry critter that enjoys filling up on our garden plants, have absolutely no desire to sample these plants.

That’s a win-win in my books.

Wild Ginger, also known as “little jug” is a good, low groundcover for eastern woodlands and shaded landscapes. It is considered a new-world native plant and the genus is well distributed around the northern hemisphere.

Before you ask, “Where have you been? Wild Ginger has been around for a long time as a garden plant.” Let me just say that I’ve been a fan of the plant for decades but for some reason have never planted it in the garden.

The above picture, for example, was taken more than thirty years ago in a nearby forest. For whatever reason, I just never got around to planting wild ginger until last season when I picked up three plants at a local horticultural society plant sale.

I’m looking forward to buying more at this year’s sale and spreading what I already have around the garden. The plant is more than capable of spreading all by itself and will quickly colonize an area through underground runners. It can also be easily multiplied through rhizome division in spring or early summer.

Propogation of Wild Ginger is by root division, seeds or even softwood cuttings.

Like most effective ground covers, Wild Ginger is very good at choking out weeds that try to invade its space.

For wildlife gardeners, native wild ginger is attractive to some butterflies but, most important, is a larval host for the Pipeline Swallowtail butterfly.

Like most woodland plants, a mulch of leaves in spring and fall is beneficial and always a wise choice.

A little about our native wild ginger ground cover

First, it’s important to make it clear that this is not a member of the ginger family (Zingiber officiale) that we love to eat. In fact, although wild ginger does have a ginger smell to it, wild ginger can be dangerous to eat. Although it has been used as a medicinal herb in the past, more recent studies suggest that the plant contains carcinogenic properties that makes it better left to simply leave it in the garden rather than use it in any dish.

Wild Ginger grows to about 6-inches tall (15 cm) with a corresponding spread of about 6-inches (15 cm) in diameter making it a great choice for those gardeners who are looking for a low-growing, tidy ground cover. Wild ginger sports two heart- or kidney-shaped leaves that stay on the plant throughout the season.

It is native to Quebec and New Brunswick through to Ontario and Minnesota and south to Florida and Louisiana. It happily grows throughout Eastern North America from zones 3 to 7.

Its range means it can be found throughout the U.S. in AL , AR , CT , DC , DE , GA , IA , IL , IN , KS , KY , LA , MA , MD , ME , MI , MN , MO , MS , NC , ND , NH , NJ , NY , OH , OK , PA , RI , SC , SD , TN , VA , VT , WI , WV). In Canada you’ll find it growing from Manitoba to Quebec and throughout Southwestern Ontario.

A dark reddish-purple flower grows beneath the two leaves that make up a single plant and remains on the plant for a short period of time in spring. You can expect a bloom to appear from April, May and even into June depending on your location.

These plants can and will self pollinate but are also pollinated by ground-dwelling insects such as beetles, ants and small flying insects.

Once the flower is spent, ants go to work gathering the seeds. They then take the seeds to their underground burrows where they provide food for the colony. In return, the ants provide an efficient form of seed distribution. Don’t be surprised to find plants sprouting up in other areas of the garden thanks to your local ant population.

Wild Ginger is best grown in shade to part shade in moist, acidic soils (pH of between 6-7). These plants do well in morning sun in cooler climates provided they get afternoon shade. It will get baked out if it gets sun all day long.

Botanists argue that there are actually two subspecies of Asarum canadense (wild ginger): Asarum Refexum, and Asarum Acuminatum. The differences can be identified by differences in the length of the calyx lobes of the flower and the amount of fine hairs on the plant’s petioles (stalks). Most, however, are simply lumped together as Asarum Canadense.

There is also an Asian species with a shinier leaf as well as a European species of wild ginger. Canada wild ginger has softer, mid-green coloured leaves that keep its colour all summer long.

Why plant a Chinkapin Oak tree

The Chinkapin Oak is a fast-growing oak that might be perfect for your back or front yard.

Fast-growing, mid-size oak that produces an abundance of small acorns

Oak trees are an outstanding addition to any garden looking to attract a variety of wildlife from deer and wild turkeys to chipmunks, squirrels, birds and a host of moths and caterpillars to feed the birds in spring and summer.

The dilemma is not, should I plant an oak, but what oak out of the more than 400 varieties should I plant.

The final decision is as much about the conditions in our yards, as it is about the look we’re after.

In our yard, the combination of sandy-based soil, a nice sunny spot and the need for a fast-growing oak that puts out plenty of acorns early in life to feed wildlife, led me to the Chinkapin Oak (Quercus muehlenbergii) also spelled Chinquapin oak.

Doug Tallamy’s The Nature of Oaks: The Rich Ecology of Our Most Essential Native Trees is an excellent resource if you’re looking for more information on these important trees.

You can also check out my posts here: The Mighty Oak, Columnar Oaks.

The Nature of Oaks is considered the bible for anyone looking for information on Oak trees.

Chinquapin Oak is a Carolinian species, common throughout the Eastern United States but found only in southern parts of Ontario that feature species from the Carolinian zone. The most common small tree and shrub species found in association with chinquapin oak include flowering dogwood Cornus florida, sassafras, sourwood, hawthorns, and sumacs.

They like an alkaline soil especially on a limestone bedrock. It’s a member of the white oak family and can live for up to 400 years.

The fact that it is rare in my geographical area and adds to the many Carolinian zone species in our yard is a pure bonus.

It didn’t hurt that the city where I live made the informed decision to give away native trees as a way to encourage homeowners to plant more native trees. Granted, my Chinkapin oak is very small and needs several years of nurturing to get to a stage where it becomes a part of the canopy and an important structural element in our garden. Once established, however, Chinquapin oaks can put on two or more feet of growth per year and grow to between 40 and 70 feet tall (30 metres) tall with a straight trunk up to 60 centimetres wide, with a similar-sized canopy.

The leaves of the Chinkapin oak are large and can grow up to 8 inches (10-18 centimetres) in length. The leaves have a scalloped look and are shiny green on the top with a dull underside. The leaves are more narrow than many traditional oaks. They are coarsely toothed with pointed tips. In the fall they turn a pleasant dark, purply-grey colour.

But the real reason I decided to plant a Chinkapin oak is the abundance of acorns borne singly or in pairs that these trees produce and the fact that production starts early in life. The acorns are smaller than typical acorns and turn almost black as they mature. They mature in one year, and ripen in September or October. Their shell is also softer than most acorns and are therefore more accessible to a greater number of birds and wildlife. The cap covers a third to half of the acorn.

In a few short years, our local wildlife is going to love it. Blue Jays, woodpeckers, our packs of wandering wild turkeys, deer, red squirrels, chipmunks, raccoons and of course birds that thrive on the caterpillars and other Lepidoptera that use the tree as a host.

These trees prefer soils in the 6.5 -7.0 up to 7.5 range. Chinkapin Oak is often confused with the swamp white oak and chestnut oak.

Those who know their oak trees, understand that Oak species, as a group, serve as host plants for caterpillars of more than 500 different butterflies and moths – more than any other genus of tree. The caterpillars (larvae) feed on the oak foliage, but do not harm the trees.

Wildlife that use the Chinkapin oak

Chinquapin oak acorns provide food for many species, including:

The high-quality acorns are a reliable food source for the red-headed and red-bellied

woodpeckers, northern bobwhite, ruffed grouse and wild turkey

white-tailed deer

chipmunks

squirrels

hummingbirds visit the flowers in spring

The trees are a larval host for the Grey hairstreak butterfly and the Red-Spotted Purple butterfly

The leaves of young chinkapin oak are commonly browsed by deer and rabbits while

beaver feed will happily feed on the tree’s bark and twigs.

If you live in an area with deer, rabbits and other rodents, you may need to protect the sapling until it is large enough to fend off the critters.

Protect your Chinkapin Oak while they are young

In our yard, I have had to protect the sapling from rabbits, deer and other rodents by placing fencing around it for a few years until it grows large enough to fend off the critters on its own.

The bark of the Chinkapin Oak is a pale brownish grey colour with thin, narrow and often flaky scales.

Flowers emerge in late spring. Trees have both male and female flowers – male flowers form as catkins, while female flowers are small and grow as individuals or in clusters.

Where do they grow naturally?

Chinquapin oak are found in well-drained soil over limestone, calcareous soils and forested sand dunes. You can expect to see them growing best on rocky sites such as shallow soul over limestone.

Fun facts about the Chinquapin Oak

Chinquapin oak acorns can be eaten raw and taste sweet.

Chinquapin oak can be mistaken for dwarf chinquapin oak as they can both grow under harsh conditions.

Chinquapin oak trees can produce almost 10 million acorns over their lifetime.

Columnar Oak: Keystone plant perfect for today’s small yards

Columnar Oaks are the ideal compromise for today’s smaller front and backyards that might be overwhelmed by massive, native Red and White oaks.

Oak trees are critical to the survival of insects, birds and other fauna

It’s no secret how important Oak trees are for a healthy, natural environment, but not everyone has space in their yard to dedicate to such massive trees.

That’s where the columnar oaks (Quercus robur ‘Fastigiata’) come into their own. These trees are smaller, more narrow and able to fit into the smallest of yards, but still pack many of the benefits that our full-size, native oaks provide.

Columnar oaks or English Oak is an Asian and European native tree. It prefers average well-drained soils in full sun, but adapts to a wide range of soil types and conditions.

These oaks can take 20-30 years before they can bear acorns – an important food source for many mammals. In the wild, it is found in northern USA and Canada.

Five reasons to plant a columnar oak tree

They are a perfect tree for small, narrow spaces in both front and backyards.

They can be used to screen out views, even on second storeys, when ground space is limited. Their branches grow low to the ground providing screening from the ground up.

Oaks are attractive to wildlife and considered a vital food source for birds as well as insects and caterpillars.

Columnar oaks are low-maintenance, trees that can withstand drought, salt and other urban issues that can stress out other, less vigorous trees.

Columnar oaks actually boast four season interest from the dark green leaves of summer, to the rusty/brown leaves of fall and beige leaves that cling to the branches throughout winter.

‘Fastigiata’ or Upright English Oak is an upright, columnar, deciduous tree that matures into a dense elongated oval shape with a short trunk. They can work as a landscape specimen or in a group to form a very tall privacy hedge.

If you are trying to decide whether or not to plant an Oak tree in your yard, The Nature of Oaks will certainly help you make that decision. This valuable book highlights the incredible benefits of these important trees.

They do best planted in full sun in well-drained acidic or slightly alkaline soil. If you live near the ocean or plant it in an area that is heavily salted in winter, these trees can continue to perform well. As an added bonus, especially during these times of climate change, the columnar oaks are also drought tolerant and can survive in more severe urban conditions. (For more on problems faced by urban trees see my articles on The Internet of Nature or How Trees Communicate.)

For more on the importance of oak trees in our garden and natural landscapes take a few moments to check out my other posts on Oak trees:

Propagation for the Columnar Oak is from seed, but don’t be surprised if the seed doesn’t always grow true.

What are the benefits of oak trees?

Doug Tallamy, renowned entomologist, advocate for native gardening and author of the book Bringing Nature Home, and the Nature of Oaks as well as a number of other highly acclaimed books on the subject, calls oak trees a “keystone plant” in our environment. This rating goes only to a select few native plants that provide food and habitat for an enormous number of insects, caterpillars and fauna that, in turn, are critical as a food source for birds and other wildlife.

In fact, oaks top the list of Tallamy’s “keystone plants.”

Tallamy cites a 2003 study that found a “single white oak tree can provide food and shelter for as many as 22 species of tiny leaf-tying and leaf folding caterpillars.” And that is just a tiny fraction of the fauna that depend on a single oak tree. In fact, the mighty oak supports 534 species of fauna, more than any other tree we can plant in our gardens.

There are about 400 species of Oak worldwide. North America boasts 90 different species with 75-80 in the United States and 10 in Canada.

Unfortunately, the emergence of smaller and smaller lots in today’s subdivisions makes planting a full-size white or red oak tree difficult for most homeowners. Although the trees are relatively slow growers and beautiful specimens in the landscape, they eventually grow to become massive trees that, if not planted with plenty of room to grow around them, might have to be removed or, at the very least, severely pruned as they mature.

How to use Columnar oaks in the landscape

This is where the columnar oak comes into its own. These trees grow tall (up to about 60 feet (18 m), but the spread is only about 15 feet (4.5m) making them the perfect tree to tuck into a narrow space say along a driveway or in a corner of the yard to provide privacy.

Our neighbour actually uses a trio of columnar oaks grouped together anchoring two blue spruce trees to provide privacy. In this instance, these trees perform more like a dense, high hedge. The combination can be stunning at different times of the year, but especially in fall when the oak leaves begin to turn a rusty brownish/red while the remaining leaves hold on to their dark green leaves into the late fall and even into winter. In the dead of winter, many of the leaves remain on the plant, not falling off until the new spring growth pushes them to the ground.

In a perfect example of a shared landscape, we benefit from the trees’ architectural interest and, most importantly, their environmental benefits as a food source for so many woodland and backyard birds. The grouping of trees provide the perfect safe habitat for a variety of song birds looking for dense cover among the deciduous oaks and the evergreen branches of the blue spruce.

Can columnar oaks be used as a privacy hedge?

Another neighbour on the street has used three of the trees down the edge of their driveway to form a narrow, but very tall and effective screen. Again, the result is a dense, natural screen that is attractive to birds throughout the summer, including winter where the remaining leaves provide a safe escape out of the cold wind and an effective roosting spot.

These columnar trees may not provide all of the benefits of our native oaks, but they are far superior to many other non-native trees that offer little to no benefits to birds and other wildlife.

If you are interested in planting one of these trees, there are a number hybridized columnar oaks available for homeowners. A search on a high-end plant nursery near me shows a total of seven varieties available.

These hybridized columnar oaks include the following: Green Pillar Pin Oak (Quercus Palustris Pringreen), Crimson Spire English Oak (Quercus Robur Crimschmidt), Pyramidal English Oak (Quercus Robur Fastigiata), Skyrocket English Oak, Kindrid Spirit Oak, Chimney Rire Hybrid Oak, Regal Prince Pyramidal Oak.

You can check out these columnar oaks, including access to detailed information on growth habits, by going to Connon Nurseries’ informative website or a website of a nursery in your location.

Sumac: First signs of fall in the garden

Staghorn Sumac is an excellent addition to the garden both to add architectural interest and provide a food source for birds and animals.

Important food source for birds and other wildlife

It’s early October and the native Sumac is already lighting up the roadsides and welcoming the first signs of fall in the woodland garden.

Along roadsides and escarpments, where this fast-growing native shrub or small tree (grows to about 30-feet high) gets plenty of sun, Sumac lights up with brilliant oranges, yellows and reds.

It’s often the first plant nature photographers focus on when in search of early colour in the fall landscape, and it’s a perfect addition to the woodland garden. Sumac has compound, serrated leaves that are a bright green in summer before taking on its fall cloak.

How did Sumac get its name?

There is no missing the velvety bark on the branches that cover Staghorn Sumac. This velvet resembles the velvet that covers the antlers of male deer (stags) throughout the summer, earning Sumac the name “Staghorn”.

There are more than 30 varieties of Sumac in North America with more native varieties in Europe, Africa and Asia.

Is Sumac a food source for birds and other wildlife?

Not only is Staghorn Sumac (Rhus typhina) an incredibly colourful addition to the woodland, its fall berries, that grow in large clusters atop the shrub’s branches, are also a very important source of high-value food for birds especially migrating birds.

Staghorn Sumac puts out small greenish-yellow flowers that attract pollinators. They grow in the shape of a cone in spring and become the reddish-haired fruit clusters as summer turns to fall.

These hearty fruit clusters, that often remain on the plant well into winter, are vital resources for hundreds of bird species including our backyard favourites like Cardinals, Gray Catbird and a host of woodpeckers ranging from the impressive Pileated to the small Downy and larger Hairy woodpeckers. Add to that list the American Robin together with other thrush species. In a more wooded natural area, don’t be surprised if it attracts Ruffed Grouse and wild Turkeys.

As an added bonus these plants are deer resistant.

Staghorn sumac is dioecious, meaning that it has individually male and female plants.

These shrubs/small trees are extremely hardy, and are both drought and salt tolerant. They prefer a sunny location and dry to moist soil and will not tolerate shade or wet soil. Use these fast growers as an erosion control plant if you have problematic areas.

Where I live, The Niagara Escarpment is the dominant geological feature that cuts through the landscape. The Staghorn Sumac lights up the many cuts through the escarpment and turns the roadsides into sparkling jewels at certain times of day.

Staghorn Sumac is native to the more southern half of Ontario, and eastward to the Maritimes.

Sumac species include both evergreen and deciduous types. They generally spread by suckering, which allows them to quickly form small thickets, but can also make the plants overly aggressive in some circumstances.

There are usually several varieties available at nurseries, but this attractive native is probably all you will need.

Other forms of Sumac

At one of my local nurseries there are three Sumacs listed including the Staghorn Sumac. The others are Fragrant Sumac, and a dwarf variety of fragrant sumac called fragrant gro low Sumac as well as Cutleaf Smooth Sumac.

Cutleaf Smooth Sumac (Rhus glabra Laciniata) is a smaller hardy shrub (hardiness zone: 2B) with finely cut tropical-looking leaves that add texture to the garden. Grown primarily for its ornamental fruit, and its open multi-stemmed upright spreading habit. It lends an extremely fine and delicate texture to the landscape and can be used as a effective accent feature. Click on the link for more information on the Cutleaf Smooth Sumac.

Gro Low Sumac is described as low growing and compact shrub with interesting foliage turning brilliant colors in fall and bright yellow flowers in spring. Makes an excellent ground cover as it tends to sucker, filling in areas quickly. Does well in shade. Click on the link for images and more information on the Gro Low Sumac.

Fragrant Sumac is described as a rugged and durable medium-sized shrub with interesting foliage turning brilliant colors in fall and bright yellow flowers in spring. Tends to sucker, forming a dense spreading mass, attractive for a garden background or for naturalizing, good in shade.

How to grow and care for native Asters

Three native asters for the natural garden that provide late-season resources for pollinators and add a beautiful textural feel into the fall.

Three native asters: Ideal plants for our natural gardens

Our native asters are stealing the show in the meadows and open woodlands around our home reminding us that, if we are not already growing them in our gardens, its time to plant them for next fall.

In our garden the wood asters have made an appearance along with the Woodland Sunflowers, goldenrod and Black-eyed Susans across the back area of our garden.

Do Wood Asters attract pollinators?

The White Wood Asters (Eurybia divaricata), also known as Heart-Leaved Aster, are delicate whitish-blue flowers that add an airy feel to the garden and the perfect excuse for the small pollinators – native sweat bees and small butterflies as well as other insects – to stop by and enjoy a late summer harvest.

New England Asters growing in a naturalistic setting. What some people may think of as a weed, are actually beautiful native wildflowers that are vital to native bees and wildlife.

Embrace these plants and the somewhat messy look they sometimes bring to your garden and focus on the wildlife that find your garden aesthetics just perfect – because it is perfect – for them.

These perennial plants grow between 30 to 90 centimetres (12-35 inches) tall, with heart shaped leaves on the lower parts of the plant and changing to more elongated and deeply serrated on the upper reaches of the plant.

For more information on native plants, check out my earlier articles: 35 native wildflowers and Why we need to grow native plants.

If you are thinking about growing your own meadow garden, be sure to check out garden designer Angela den Hoed’s meadow garden and her five favourite plants for the meadow garden.

White wood asters, New England asters combine beautifully with goldenrod.

How to grow Wood Asters

These are a form of shade-loving asters that can be found growing naturally in dry, organic-rich woodlands and on the edges of forest areas in part shade.

Ours are growing happily on the edge of our ancient crabapple trees, where conditions seem almost ideal for them.

Although these asters will tolerate full shade or sun, they are happiest in part shade. Their beautiful, yet delicate branching clusters of pale blue flowers give a nice airy feel to the garden as well as providing a good source of nectar and pollination for both bees and butterflies.

Hardiness Zone: 3-7

Light: Part shade to full sun

Moisture: Tolerates dry soil, shade to part shade neutral to slightly acidic conditions.

Soil: clay loam to sandy loam, organic

Mature Height: 3-feet-high

Growth: Vigorous or aggressive, even in dry shade.

Propagation: Can be started from seed (seeds mature in late fall), by dividing clumps in early spring or allowed to spread entirely on its own.

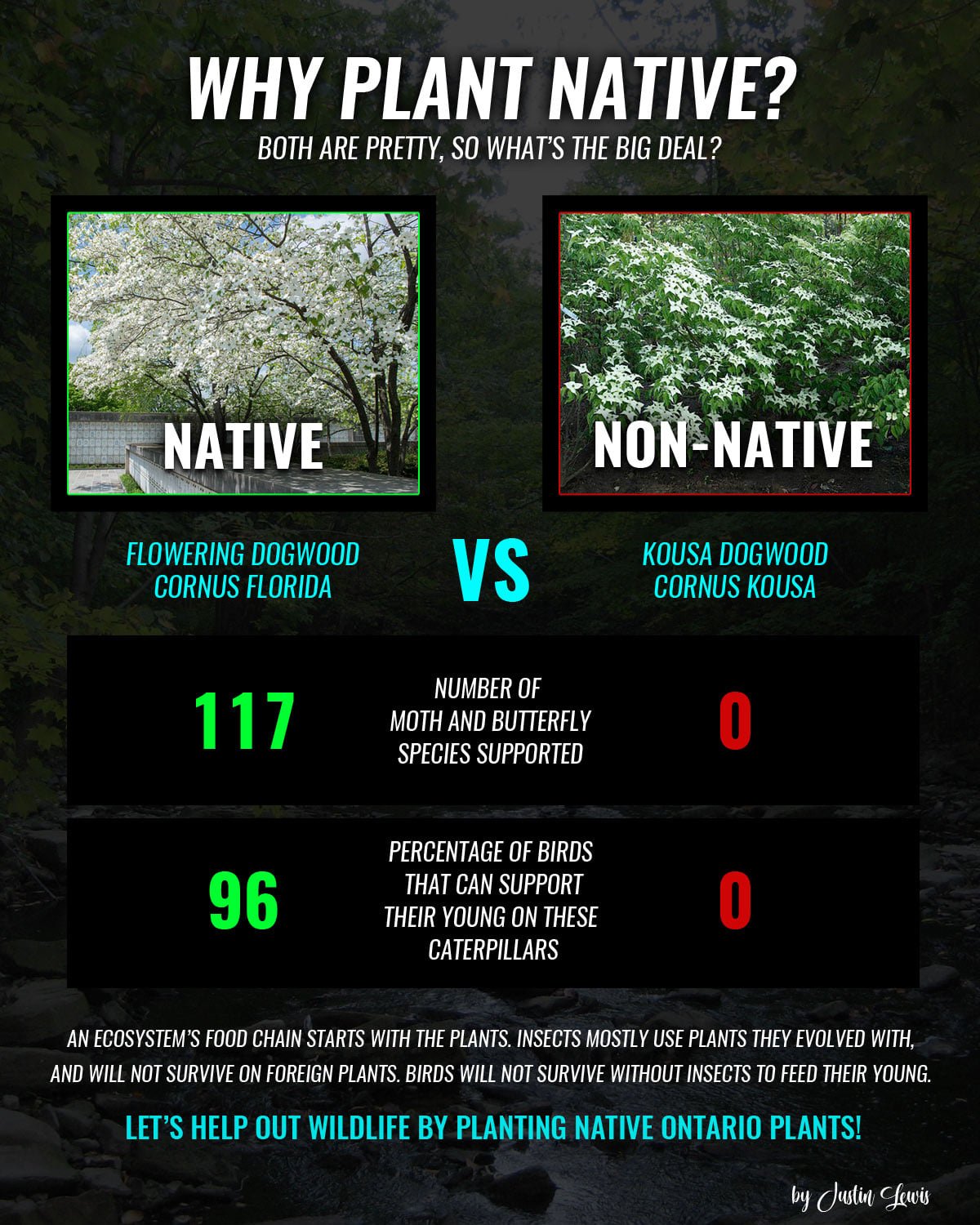

This informative infographic designed by Justin Lewis shows the value of the New England Aster.

Are Wood Asters a threatened species?

The Wood Asters’ range is quite broad despite its extremely limited range in Canada where it is confined to a small number of sites in the Niagara region and in more southern areas as well as a few woodlots in southwestern Quebec.