Native Eastern columbine: Growing tips for a woodland, wildlife garden

The Native Eastern Columbine is an early blooming red and yellow wildflower that is an important food source for returning hummingbirds and other pollinators. Grow them in your woodland wildlife gardens in average to poor soils in rock gardens, woodland edges or garden borders.

First columbine encounter on Niagara Escarpment

I’ll never forget my first sighting of wild native columbine.

I was hiking along the Niagara Escarpment with my camera and stumbled upon two beautiful clumps of the native plant, columbine, in their prime and growing on the edge of an overhanging, steep cliff.

I had to get a shot of them. So, being young and not too bright, I moved way too close to the cliff’s edge to get the images.

Needless to say I got the shots and survived to tell you about it.

Not the best shots maybe, but ones I’ll never forget.

These wildflowers made such an impression on me that day that native columbines were the first wildflowers I planted in our front woodland wildlife garden more than ten years later.

(For my article on why native plants are vital in our gardens, go here.)

Although the Eastern Columbine may look delicate, the plants are actually quite hardy, living for many years, often in quite harsh environments. When I say my first sight of them was growing on a cliff, I wasn’t kidding. These delicate-looking flowers appeared to be growing right out of a crack in the granite cliffs.

Not only did I plant them in my front garden, I also recreated in my garden – at least as best I could – that same image of the columbines growing on the limestone edge of the escarpment.

Our native columbines grow out of, and next to, a large limestone boulder surrounded by clumps of maidenhair ferns. I originally tucked the plant right up beside the edge of the boulder so that it could draw heat from the rock in early spring. It wasn’t long, however, before a plant emerged from a thin pocket of soil along a crack in the rock. These little guys will find a spot to grow anywhere they can. This plant stays more compact than the one growing in the soil beside the rock, but together they create much the same feeling I experienced so many years ago overhanging the cliff.

Don’t mistake the native Eastern columbine for a delicate wildflower. These early spring bloomers can be found growing in some harsh areas, even out of granite boulders in my front yard or on cliff edges.

Native wildflowers that combine well with columbines

The Eastern columbines looks right at home growing alongside other native woodland plants. Besides the maindenhair ferns, mine also share space with Solomon’s seals, foamflowers and bloodroot where they make an attractive early-spring combination with other woodland natives.

Our native Columbines can also look stunning growing in large swaths all on their own or in large garden borders as a middle-height plant where the flowers growing atop the plants provide an almost ethereal feeling.

The columbines and maidenhair ferns both like moist, well-drained sandy, limestone-based soil. If the columbines are planted in too rich garden soil, don’t be surprised if they put on excessive vegetative growth with weak stems. Instead, plants in sandy-type soils will prosper and grow in a more tight, compact form, surviving for many years. They prefer partly-shaded woodland habitat with calcareous soils that are not too rich. A single plant, while in bloom, can put out a large number of flowers. Columbines will naturalize under the right growing conditions and in a woodland or native plant garden.

Native Eastern Columbine in the garden mixed with ferns, epimediums and sedum.

The Eastern red Columbines, also knows as the wild red columbine, or Canadian columbine, is a relatively low maintenance plant that is actually in the buttercup family (Ranunculaceae). Spent flower stalks can be clipped off to tidy up the plant, but don’t cut the plant back to the ground in case it is being used by host larvae.

Columbines can be attacked by leaf miners that leave serpentine trails in the leaves. They are generally harmless to the native plants.

In the wild, native columbines can be found in open woodlands and rocky areas throughout North America. In Canada they stretch from Nova Scotia to Saskatchewan in zones 2-9. It can also be found through much of the eastern United States.

Because these perennial plants, which grow 20 to 30 inches high, are self propagating, my original planting years ago continues to self seed in the same general vicinity where they were originally planted. More native columbines, were planted last year in a shaded area of our back wildflower garden.

Backlit columbine in spring.

Native columbines, know as the Eastern Red Columbine (Aquilega canadensis L.), bloom from April to July in rocky open woods and slopes, and provide an early nectar source for hummingbirds. The flowers are actually a critical food source for returning ruby-throated hummingbirds in spring where they tend to bloom for about a month beginning in May or June depending on weather conditions.

The Eastern Columbine can grow up to 4 ft. tall but don’t be surprised if yours stay much more compact. You can expect the plants to be more in the 6-12 inch zone if grown in shady woodland consditions in average soil.

The showy, nodding red and yellow flowers have five hollow spurs that point upward and contain nectar that is particularly attractive to hummingbirds and other long-tongued insects. Because the flowers point downward, hummingbirds and insects including bees, butterflies and hawk moths have to come up from below the flowers to obtain the nectar.

Finches and buntings are known to consume the small, shiny black seeds that are contained in five pod-shaped follicles after the bloom period.

The columbine is larval host to the Columbine Duskywing skipper found in Southern Ontario and throughout the Eastern United States. The female skipper deposits eggs under the leaves of the native columbine where tiny caterpillars feed on them until they emerge as the small dark brown, nondescript skippers.

I have found that both the deer and rabbits leave these native plants alone in our zone 6-7 garden. In warmer areas, where the plants are considered evergreen, this may not hold true.

The light green to blue-green leaves of the Columbine are divided and subdivided into threes. The foliage is attractive even when not in bloom and turns yellow in fall.

Our native wildflower can be described as an attractive, old-fashioned plant, but it’s not without its accolades. This erect, open herbaceous perennnial plant has received the Royal Horticultural Society’s Award of Garden Merit.

That makes it a worthy consideration for a spot in your garden. I grow mine both in the front and backyard.

Don’t mistake the very showy European Columbine (A. vulgaris), with their blue, pink, violet and white short-spurred flowers, with our native variety.

The Canadian Wildlife Federation website also lists the following native columbines for consideration depending on the growing zones where you live.

Sitka columbine (A. formosa)

Native to: southern Yukon, B.C. and swAlta.

Habitat: moist to dry open areas such as streamsides, rocky slopes, woods and meadows at subalpine elevations (moist alpine meadows and mountain meadows)

Appearance: up to about one metre (three feet) tall, nodding red flowers and short spurs

Yellow columbine(A. flavescens)

Native to: B.C. and swAlta.

Habitat: moist meadows, screes/slopes and acid rocky ledges at moderate to high elevations (up to just above timberline and higher than A. formosa)

Appearance: a pale yellow flowering columbine with long spurs, sometimes with a pinkish tinge, blooming from late June to early August. Nodding flowers.

Jones’ columbine(A. jonesii)

Native to: swAlta.

Habitat: subalpine limestone screes and crevices

Appearance: a low-growing plant that reaches five to 12 centimetres tall, with leathery, hairy leaves that bunch together to resemble coral. It has only one or two short-stalked flowers that are a blue and typically face upwards.

Blue columbine (A. brevistyla)

Native to: the Yukon, B.C., Alta., Sask., Man. and central Ont.

Habitat: This boreal forest species of columbine grows in rock crevices, meadows and open woods.

Appearance: blue and white flowers, nodding/upright with short spurs

More links to my articles on native plants

Why picking native wildflowers is wrong

Serviceberry the perfect native tree for the garden

The Mayapple: Native plant worth exploring

Three spring native wildflowers for the garden

A western source for native plants

Native plants source in Ontario

The Eastern columbine native plant for spring

Three native understory trees for Carolinian zone gardeners

Ecological gardening and native plants

Eastern White Pine is for the birds

Native viburnums are ideal to attract birds

The Carolinian Zone in Canada and the United States

Dogwoods for the woodland wildlife garden

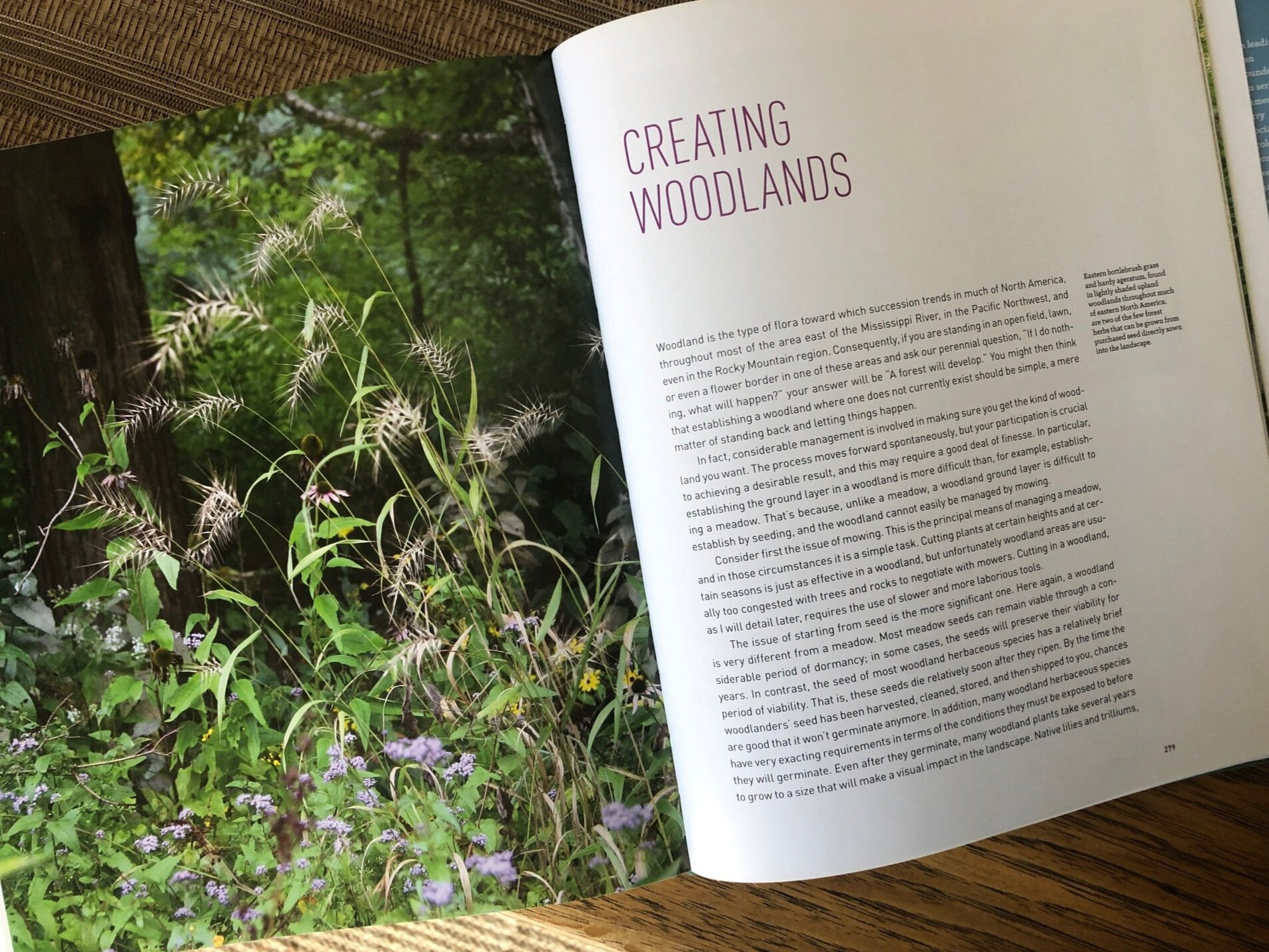

Garden Revolution: Ecological gardening made easy

Garden Revolution joins a growing list of informative books calling for a new ecological approach to gardening. It is a book that will change the way future gardeners approach their land not only because it encourages a more ecological approach but because it shows them an easier and simpler way to manage their gardens big or small.

Garden design book is guide to low-maintenance landscape

It’s not everyday you come across a book that changes the way you think and the way you do things.

Garden Revolution just may be that book.

The full title of the book, published by the highly respected garden book publishers Timber Press, helps provide a better idea of where the authors were going when they wrote the book: Garden Revolution: How our landscapes can be a source of environmental change.

I like to think that the authors and I have been on the same wavelength for the past decade or two, with the only difference being that they took it to a level far beyond anything I could imagine.

The book is just another illustration of why using native plants, trees and shrubs in our landscapes is not only good for the environment, but for our own gardening success.

For my article on why using native plants in the garden is important, go here.)

The basic premise of their philosophy being: Let nature do most of the work.

One of the last chapters in the book focuses on the steps needed to create and maintain an ecologically-based woodland garden.

The result: A low-maintenance ecological garden design that takes most of the work out of the installation and management of even large landscapes.

It’s an approach I have been interested in for years and have certainly been practising in my own woodland/wildlife garden, much to my neighbours’ chagrin. In my case, laziness plays a major role. The authors, on the other hand, use Mother Nature on a grander scale to control huge expanses of meadow, shrubs and woodland gardens using mostly native plants that would be impossible to maintain with traditional garden approaches and methods.

And the results are often stunning.

Don’t take my word for it. Doug Tallamy, native plant guru and author of Bringing Nature Home and The Living Landscape, puts it simply: “This beautiful book shows us that guiding natural processes rather than fighting them is the key to creating healthier landscapes and happier gardeners.”

“This beautiful book shows us that guiding natural processes rather than fighting them is the key to creating healthier landscapes and happier gardeners.”

Tallamy goes on to describe the book as “an essential addition to our knowledge of sustainable landscapes.”

The authors, Larry Weaner and Thomas Christopher surely know of what they write about in this beautifully illustrated coffee-table book boasting more than 320-pages of garden knowledge, shortcuts and solutions to so many of our garden issues.

Weaner, a leader in North American landscape design and founder of the educational program series New Directions in the American Landscape, is owner of a highly successful landscaping firm well known for combining ecological restoration with traditions of fine garden design. It’s so successful, in fact, that it has received the top three design awards from the Association of Professional Landscape Designers.

His co-author, Thomas Christopher, is the author of several gardening books and a graduate of the New York Botanical Garden School of Professional Horticulture. He has been creating gardens for clients for forty years.

Together they present a convincing case for adopting ecological principles to create living landscapes that are both alive with colour, while at the same time being extremely friendly to local wildlife.

As the authors point out in the book’s introduction: “For all of those (gardeners) galvanized by the message of such environmental gardening manifestos as Sara Stein’s Noah’s Garden and Doug Tallamy’s Bringing Nature Home, this book is the next step, the way to turn philosophy into practice.

In their “alternative approach” to garden design and maintenance, the authors set out to prove that: “less is truly more. Minimizing intervention and letting the indigenous vegetation dictate plant selection and, as much as possible, do the planting, producing a garden landscape that flourishes without the traditional injections of irrigation and fertilizers and is better able to cope on its own with weeds and pests.”

They tackle the task by first guiding us through the learning process. They introduce readers to the importance of ecological gardening, and work to convince them to play a part in reversing the harmful habits into which much of gardening has fallen.

“There are powerful environmental reasons for bringing our gardens into a sounder relationship with nature,” writes Weaner, who goes on to explain that he realizes that doing the right thing is not necessarily going to convert the majority of gardeners. Instead, he focuses on a more selfish motif – getting out of doing work.

“I honestly believe that having once sampled an ecologically driven approach, gardeners won’t want to do anything else. For me the most persuasive reasons are that it’s easier and far more rewarding to transform the human landscape in this fashion.”

If you are looking for a gardening book, be sure to check out Alibris for a great selection of ne and used books.

• If you are considering creating a meadow in your front or backyard, be sure to check out The Making of a Meadow post for a landscape designer’s take on making a meadow in her own front yard.

Five lessons to learn from this book

• It’s important to work with nature rather than against it. As the authors points out, gardeners who follow the advice of the book will learn to “form a partnership with nature.”

• Refrain from tilling the soil or doing any other action that will disturb the top layer of soil and free weed seeds lying in wait to sprout. This includes pulling out weeds. Better to cut weeds off at soil level to starve them of sunlight than to pull them out and expose previously buried seeds and open the soil up for future weed growth.

• Whenever possible, encourage existing native plants to reseed themselves around the garden especially in large swaths of open meadows.

• Most land in North America wants to return to forest if left alone. In other words, if we do nothing to manage our property, it will, over time, return to a woodland.

• In typical woodland garden, there are three distinct zones – the interior, the edge, and the canopy gaps. Within these zones, there are 4 vertical layers to consider: The upper canopy layer, understory tree layer, shrub layer, and ground layer. If any of these layers are missing, they must be returned to the woodland.

Their ecological approach does away with most tilling, weeding, watering and fertilizing plants. Tilling, for example, only opens up the soil for existing weed seeds to germinate. Spending hours weeding is again a counter-productive endeavour because it once again exposes the soil to ever more weed seeds. Instead, their approach is to leave the soil undisturbed as much as possible and encourage plants to reseed naturally without much if any intervention on the gardener’s part.

Rather than digging out weeds, it’s better to simply cut them off at soil level to restrict photosynthesis. Eventually, more dominant plants can be used to crowd the weeds out.

This ecological approach, while feasible on a small scale, really comes into its own on large-scale gardens that cover acres of open fields, scrub lands and forests.

In the chapters on design, the authors tackle site analysis, creating a master plan for the garden, and developing a synergistic plant list.

Then the fun really begins. In the Field chapters, readers begin to understand how the ecological process plays out. It’s fascinating to read the real-life experiments and results the author has watched unfold in his many projects and how the traditional landscaping industry began to recognize the value in this revolutionary approach.

Three garden types to explore

Three key chapters explore the most dominant naturalistic-styles: The creation of meadows and prairies, the creation of shrublands, and finally the secrets to creating successful woodlands.

The process behind the creation of a woodland is of particular interest here, so we’ll explore that in a little more detail.

Not unlike Mary Reynold’s book The Garden Awakening, (see earlier post) The authors of Garden revolution start with the premise that if left to its own devices, most open land, whether it’s a meadow, scrub land or perfectly manicured lawn, will return to a woodland.

In other words, the authors write: “If I do nothing, what will happen?” your answer will be “A forest will develop.”

The problem is, a considerable amount of management is needed to ensure that a proper woodland emerges. The first problem is establishing the ground layer in the woodland. Unlike a meadow, which can be managed primarily by mowing at different heights and at different times of the year, Woodlands are too congested with trees and rocks to use mowers.

The herbaceous species on a woodland floor often have very specific needs in terms of proper soil and seed germination. Add to that the fact that even after they germinate, many woodland plants take several years to grow to a size that will make a visual impact in the woodland.

Complicating the process further is that most woodlands have three distinct zones – the interior, the edge, and the canopy gaps. The type of trees in the woodland will play a major role in the levels of shade in the interior of the woodlands. That, in turn, will play a role in the types of plants (both invasives and non-invasive) that will take up residence there. The decision to increase tree density or thin-out the woodland will depend on whether the existing vegetation is largely native or primarily an invasive, exotic species.

These are just a few of the difficulties faced in the creation of the woodland garden.

Layers in the woodland garden

Important too are the vertical zones of the woodland.

“You should also examine the vertical layers within the woodland to determine which, if any, are missing or sparse and, if so, why.” Deer, invasive species, and human activities may all be responsible for the destruction of any one or more of the layers.

The authors provide detailed explanations of the four layers of the woodland garden and explain that any that are missing need to be replaced by the gardener.

The four layers are described as:

• canopy tree layer, which is the topmost layer, the interlacing of branches and foliage that shades all below them.

• understory tree layer, which consists of both permanent understory trees like serviceberry, pawpaw, and dogwoods, as well as saplings of future canopy tree that occupy the space only temporarily.

• shrub layer, which consists fo the shrubs that flourish under and among woodland trees; and

• ground layer, the lowermost layer consisting of herbaceous or prostrate woody plants on the woodland floor.

The chapter goes on to explore in detail everything from managing the woodland, to woodland soil, planting for natural succession, the use of pioneer trees to foster mature forest species, and natural recruitment.

In the end, the authors, in describing the “Big Picture” explain that: “when working with estblished woodland, your initial goal should be to transfer the vegetation from exotic, invasive species to a flora dominated by native ones. Once this has been accomplished, you may take as your subsequent goal to translate the vegetation from generalist native species to more specialist natives.”

Okay, this all sounds like a lot of work to me. What happened to letting Mother Nature do all the work?

I guess it all depends on how far you want to take your woodland, meadow or shrub garden.

As the authors explain: The phrase “a partnership with nature” has been around for a long time, and I never paid it much attention. From a practical standpoint, I really didn’t know what it meant. Now I think I do.”

This partnership with nature is something every gardener needs to embrace. Working with nature rather than against it, is not only good for the environment but it will make our lives much simpler, our gardens easier to manage and the wildlife we share with it much happier.

Do yourself a favour and get this book. Read it. Study it, and read it again.

Adopt the philosophy. Have a glass of wine or another cup of coffee and relax.

More links to my articles on native plants

Why picking native wildflowers is wrong

Serviceberry the perfect native tree for the garden

The Mayapple: Native plant worth exploring

Three spring native wildflowers for the garden

A western source for native plants

Native plants source in Ontario

The Eastern columbine native plant for spring

Three native understory trees for Carolinian zone gardeners

Ecological gardening and native plants

Eastern White Pine is for the birds

Native viburnums are ideal to attract birds

The Carolinian Zone in Canada and the United States

Dogwoods for the woodland wildlife garden

Bringing Nature Home by Douglas Tellamy

A little Love for the Black-Eyed Susan

Native moss in our gardens

This page contains affiliate links. I try to only endorse products I have either used, have complete confidence in, or have experience with the manufacturer. Thank you for your support.

White pine: Native evergreen that helps birds and wildlife

Our native Eastern White Pine is an elegant, open evergreen that deserves a place in more gardens. The tree’s beauty is evident in its early stages. The fast-growing tree eventually becomes a stately, flat-topped tree that has captured artists for years. It is also an important tree to attract wildlife to our backyards.

White pine is showstopper in Carolinian forest

The eastern white pine just might be the single greatest tree for the woodland and wildlife garden.

There, I said it. And I’ll stand by it too.

In fact, our native pine tree (Pinus Strobus) is not only beautiful in every stage of life, it also provides nesting habitat, food and shelter for numerous backyard birds. This alone would make it a standout on most lists, but add the fact it looks as good in spring, summer and fall as it does in the coldest of winters, when neighbouring trees are stripped of their leaves, and you’ve got yourself a real winner.

The Eastern White Pine is the only pine species that is native to the Carolinian Zone of Southern Ontario.

(For more on the importance of growing native trees, plants and shrubs in our gardens, go to my article here.)

It grows in zones 2 to 7 making it the perfect addition to many Canadian and American woodland and wildlife gardens looking for a tree with four-season interest. In the forests of Eastern Canada, the white pine stands above the rest growing taller than any other tree.

It’s too bad not enough gardeners celebrate our native pine and Ontario’s Provincial tree enough to plant it every chance they get.

How close should White Pine be spaced apart?

I’m a firm believer that too many plant nurseries and even experts recommend planting trees and shrubs too far apart in order to give them room to grow. That’s fine if you want to treat the tree or plant as a specimen, but if you are looking for a more full or dense planting closer to a more natural look, ignore these recommendations and plant a little closer.

White Pine are recommended to be planted about 6-feet apart in all directions. That’s perfectly fine, but if you are looking to use them more as a hedge or screen, consider planting them maybe 4 feet apart knowing that they will be growing together in a few years.

The elegance of the Eastern White Pine is evident here with its feathery, blue-green needle clusters and pine cones.

Quick Fact: The University of Guelph Arboretum’s Century Pine Collection is made up of pines that were planted in 1907 and is likely the oldest pine plantation in Canada.

A trip to the local tree nursery often highlights a host of ornamental varieties of our native pine, but few, if any, species examples. (See a partial list of ornamental varieties at end of article)

I’m not sure why so many gardeners often choose a more dense-looking tree like the blue spruce rather than the open, airy feel of a young eastern white pine.

Gardeners may also hesitate to plant the fast-growing tree that typically grows 50 to 80 feet in cultivation, but will grow to between 100-150 feet tall in the wild, with the record holder coming in at 200 ft tall.

So it goes without saying that the white pine is best suited for landscapes with ample space. Don’t let that stop you from squeezing one into your backyard landscape. The size of the trees can be managed somewhat with regular pruning.

I remember my first real introduction to the white pine. I was aware of its elegant branches from my many hikes in local woods and travels to Northern Ontario where the tree often dominates the landscape. In those days, however, I was more concerned with getting photos of the wildlife than admiring the trees. If there was not a bear sitting in the branches, I was not really interested in it.

However, they certainly left an impression on me. To this day, the trees are a vivid reminder of many memorable moments spent wandering Algonquin Park in search of moose, deer, beaver and anything else that would present itself to my camera.

It’s not hard to understand why the Eastern White Pine is a favourite spot for large birds like owls, hawks and eagles to roost in during the day.

It wasn’t until I began to acquire an appreciation for plants, trees and natural landscaping that I really noticed the beauty of the eastern white pine.

A landscaper shared his love for the tree with me during a tour of some of his projects. I remember how he used several of the trees packed close to one another to form a feathery background for a small waterfalls and pond. The trees were pruned to thicken them up and perfectly screened a nearby wooden privacy fence.

The scene, in the middle of a typical, small suburban backyard, took me right back to my days of hiking in northern Ontario.

It also taught me that using large trees on small lots and pruning them to create the shape and size you are after can turn a basic backyard into a woodland retreat one would expect in the heart of northern Ontario or New York’s Adirondacks.

His pruning techniques showed me that there is also a simple solution to the rather open white pines that many gardeners shy away from purchasing. By simply nipping off a third of the candle growth in spring, before they open, the tree will thicken up over time and provide an elegant, blue-green coniferous tree that is equally at home as a specimen in your garden as it is being used in numbers to form a screen or hedge.

Get garden ready over winter

Three years with a bad hip made my ability to work in the garden extremely difficult. Following a hip replacement, I knew I had a lot of work to do to prepare myself for another garden season, and the best way to achieve that was to begin walking.

If you need to either get in shape for gardening or lose a few pounds, I highly recommend walking your way to health. Today, I walk 12,000 steps a day and I owe my new found health and ability to work in the garden to two devices – a Fitbit and Nordic Walking Poles.

The Fitbit allows you to track your increasing fitness levels, while the Nordic Walking Poles not only provide a full-body workout, but they also help you exercise longer while reducing stress on both your knees and hips.

A close-up of the tree’s pine cone.

Five White Pine facts

• The Eastern White Pine is a long-lived species that can live up to 200 years or more.

• The tallest tree has been recorded at 200 feet high, but most mature trees growing in the wild can reach 150 ft high and more than three feet in diameter.

• The trees have long been sough out as a traditional Christmas tree, prized for their conical shape and soft, feathery needles.

• Pine needle tea has a pleasant taste and smell and is rich in vitamin C (5 times the concentration of vitamin C found in lemons. Vitamin C is an immune system booster which means the tea can help battle illness and infections.

• Take a handful of pine needles and let them soak in boiling water on the stove. The aroma will add a nice pine smell in the house. Perfect for any time but especially around the Christmas season.

How important are the trees to wildlife?

Just how important is the white pine to our gardens and its wildlife? Doug Tallamy, chairman of the department of entomology and wildlife ecology at the University of Delaware, and author of Bringing Nature Home and The Living Landscape, considers the white pine one of the best native trees for providing food, nuts and insects for a host of wildlife.

His hypothesis for the gardener’s lack of enthusiasm toward the white pine is the tendency for the tree to lose its main leader to ice storms when grown in the open as a specimen. The result is a spreading flat-topped tree.

Anyone familiar with the Canadian Group of Seven artists, however, know full-well that it is this flat-topped look that inspired many of their greatest landscape paintings including A.J. Casson’s 1957 painting entitled “White Pine.” A perfect illustration of how the pines take on their elegant flat-topped look as they age. This link shows the painting.

Quick Fact: This tall and stately conifer was once a favourite for ship masts as well as furniture building.

“Every creature is better alive than dead, men and moose and pine trees, and he who understands it aright will rather preserve its life than destroy it.”

If grown in a sheltered forest setting with rich soils, the eastern white pine can become huge with large straight trunks. Although it often goes unnoticed in the woodland setting, a recent drive through the forest around our home revealed a stunning number of natural white pine in various stages on life.

It is the host plant for the Eastern Pine Elfin and used extensively by the imperial moth. The Pine Elfin is a rather drab brownish butterfly, which is found in most of the eastern U.S. and in Canada from the Atlantic provinces through Ontario, southern Manitoba, central Saskatchewan, and into Northern Alberta.

The imperial moth is one of the largest and most impressive in its range. Although more common in the southern United States it can be found as far north and the southern Great Lakes.

Pine needles in general are favourites of 203 species of moth and butterfly larvae.

The Audubon Society reports that seeds found within the pine cones are food for up to forty species of birds (including blue jays, brown thrashers, cardinals, chickadees, nuthatches, grosbeaks, juncos and woodpeckers) as well as red fox and gray squirrels, chipmunks, mice and voles. Expect to wait between 5-10 years for the brown cones (4-8 inches long) to be produced on the tree.

In fact, the seeds are an important food source for crossbills which will even migrate from Canada to the United States during some winters in search of white pine seeds.

Pines, including the white pine, are also home to sawfly caterpillars, a staple of many birds in early spring looking to feed their young.

Is there any doubt that you need a couple of these white pines for your backyard?

If so, consider that the soft, feathery foliage of the White Pine is an excellent source of nesting material. In fact, when setting up a bluebird box it is often recommended to use a handful of white pine needles in the boxes to attract a nesting pair.

The white pine offers refuge for birds during cold winds and snowstorms, as well as relief from extreme sun and heat during summer months.

Owls, hawks and eagles often perch in the trees to take advantage of the views the open branches of mature specimens provide. Eagles are known to prefer a mature, flat-topped pine for nesting.

Botanical Name: Pinus strobus

Common Names: Eastern white pine

Plant Type: Needled evergreen tree

Mature Size: 50 to 80 feet tall, 20- to 40-foot spread

Sun Exposure: Full sun to part shade

Soil Type: Medium-moisture, well-drained soil

Soil pH: 5.5 to 6.5 (acidic)

Hardiness Zones :2 to 7 (USDA)

Native To: Southeastern Canada, eastern U.S.

Mourning doves, purple finches and robins also use the open branches as favourite nesting sites.

Although the white pine is an excellent ornamental tree, it requires favourable growing conditions to thrive. Grow it in fertile, moist, slightly acidic, well-drained soil in full sun. They will tolerate some shade, but will not do well in hot, dry, infertile, compacted, alkaline or heavy clay soils.

What native plants grow beneath a white pine?

If you have ever looked under a white pine, you would be hard pressed not to notice the abundance of dried needles that form a thick mulch. The needles not only form a mulch, they also help to create a somewhat more acid environment under the tree. This together with a lack of water adds to the difficulty of growing plants under the pine.

Consider using these plants under your tree: Bearberry, Wild Ginger, Columbine, White Woodland Aster, Heart Leaved Aster, Wild Geranium, Woodland Sunflower, Mayapple, Jacob’s Ladder, Solomon’s Plume, Starry Solomon’s, Goldenrod and Bellwort.

Native ferns that can be used include: Maidenhair Fern, Lady Fern, Oak Fern and Royal Fern

Road salt and other elements that can harm white pines

Don’t plant your pine close to busy streets. They are susceptible to damage by road salt as well as air pollution and drying winds. The branches can suffer severe damage in ice storms and heavy snow.

If planted in less than ideal conditions, young and recently planted trees can suffer from white pine decline, characterized by a decline in needles until they have only small clusters of stunted needles at their branch ends. This is a signal to move the tree to more ideal locations in the garden.

Other problems include white pine root decline, blister rust disease (caused by gooseberry or wild currant bushes growing nearby), white pine weevil, European pine shoot beetle and European pine shoot moth.

Don’t let any of these potential problems stop you from planting this native.

Nothing, not even the white pine, is perfect.

The pine trees seen here are being used as a screen on this larger rural property to block the view of the house.

White Pine cultivars

Blue Shag – is a dwarf, dense, eastern white pine ideal for use in rock gardens, as a foundation planting or in a shrub border.

Fastigiata – is a small to medium-sized cultivar with a narrow, upright, columnar habit. Grows 30 to 40 feet tall, but only 10 feet wide. The tree’s shape broadens with age.

Hillside Winter Gold – is a fast growing upright, full-sized cultivar with an open, pyramidal habit. Typically grows 12 to 15 feet over the first ten years, eventually reaching 30 to 70 feet tall.

Horsford – a dwarf cultivar that has a dense, rounded growth pattern and grows slowly (3 inches per year) to form a miniature mound of foliage to 1 foot tall. Works well as an accent in the rock garden.

Macopin – is a broad upright, irregular, compact, shrubby form which grows at an intermediate rate (6 to 12 inches per year) to 3 feet tall by 3 feet wide (sometimes larger).

Pendula – is a semi-dwarf cultivar with weeping, trailing branches that may touch the ground. It typically grows to 6 to 15 feet tall with a larger spread.

Pinus strobus (Nana Group) – is used by many nurseries as a catchall term for describing a group of compact, shrubby, mounded, irregularly branched, spreading, dwarf forms of eastern white pine. These plants are very slow growing, often reaching only 2 feet tall after 10 years. They eventually mature to 3 feet tall by 4 feet wide, but less frequently may reach 4 to 7 feet in height and 6 to 10 feet in width. Silvery, blue/green needles are soft to the touch.

Loui – Boasts a golden-green colour years round and comes highly recommended from a reader.

More links to my articles on native plants

Why picking native wildflowers is wrong

Serviceberry the perfect native tree for the garden

The Mayapple: Native plant worth exploring

Three spring native wildflowers for the garden

A western source for native plants

Native plants source in Ontario

The Eastern columbine native plant for spring

Three native understory trees for Carolinian zone gardeners

Ecological gardening and native plants

Eastern White Pine is for the birds

Native viburnums are ideal to attract birds

The Carolinian Zone in Canada and the United States

Dogwoods for the woodland wildlife garden

As an affiliate marketer with Amazon or other marketing companies, I earn money from qualifying purchases.

Building your Woodland: One Tree at a time

Dream of what your woodland garden can be and we will work together to make it real. By using native and non-native trees, plants and flowers, you can transform your garden into a wildlife haven. Then spend the day photographing the nature around you.

Woodland wildlife garden needs time to mature

A woodland garden can be as big or as small as you want. Start with a single tree in your yard and try to imagine what that tree can become.

Remember a woodland garden can take time to mature into perfection. Like a freshly-built home that lacks the layers living brings to it, a woodland needs that same time to develop the multiple living layers that make it the inviting place we want to experience. It too needs its spirit; one that starts deep in the soil and stretches high into the upper layers of the forest canopy. If you are just starting out developing your woodland garden design, the first rule to understand is that a woodland garden is all about layers. Three layers really, but you could argue four even six and still be correct.

It all starts with the upper canopy

The top layer, the upper-level canopy, is what builds the strength of the woodland over time. If you do it right, the middle layer is where much of the beauty resides. Then there is the shrub layer and finally the ground layer, also not without its share of beautiful things. The ground layer, appropriately made up of ground covers, forms a protective layer that encourages all that is above it to prosper.

Early morning offers a different experience in the Woodland for both photographers and dreamers. Get up early, catch the light, and sneak in an afternoon nap.

Maybe, if you are like me and bought into an older neighbourhood, you are already blessed with a mature tree or several that helps to create the critical upper canopy. If you are not blessed with any large trees on your site, that large maple growing in your neighbour’s yard casting its lovely shadow over your yard will do the trick too. Remember though, your neighbour could cut that tree down and your upper canopy can disappear in an afternoon. Better to plant your own as soon as possible as a backup to your grumpy neighbour’s tree.

This photo illustrates the layering of our mature woodland garden. A large locust and tulip tree form the upper canopy, while a mautre Cornus Kousa in full flower forms part of the mid-canopy. The kousa is joined by serviceberry, redbuds and Cornus Florida in the lower canopy of this area of the garden. Ostrich ferns fill in as the primary ground cover.

Large trees form the upper canopy

When we talk upper-level canopy, we’re talking the big boys of the tree world.

Think maples, locusts, lindens, oaks and a host of other native trees that will grow large enough to eventually tower over the garden.

If you live in the Carolinian zone (link to my post) or a similarly appropriate area and need a quick canopy, consider planting a couple of Tulip trees. They are fast-growing native trees, growing up to 35 metres tall. In fact, they are among the tallest and straightest trees in the forest. In fact, they were often the tree used as telephone poles because of their straight growth habits. Their canopy can be trimmed up high as they shoot to the sky, and the shade they throw is open enough to allow understorey plants to grow happily.

Tulip trees have a spectacular yellow-green 5 centimetre long spring blooming, tulip-shaped flowers. Although the fast-growing tree is not the best host of insects and caterpillars that provide food for birds, the seeds of the tulip tree grow every year and are a source of food for birds and small mammals.

Oaks are kings of biodiversity

If you are looking for the perfect tree to form your upper canopy, you would be hard pressed to do better than one of the mighty oaks. Consider planting an oak near your tulip trees where it will grow up to provide a future canopy after the tulip trees have served their immediate goal of providing a fast and effective canopy in the short-term.

What makes Oak trees so important?

As Douglas W. Tallamy explains in his book Bringing Nature Home: How you can sustain wildlife with Native Plants, (link to my review of the book) a single white oak tree can provide food and shelter for as many as “22 species of tiny leaf-tying and leaf-folding caterpillars.” These combined with all of the other “lepidopterans (moths and butterflies), heteropterans (true bugs), homopterans (aphids, plant hoppers,and scales), thysanopterans (thrips), orthopterans (katydids, grasshoppers, and crickets), … that develop on white oaks are considered s well, you can appreciate how important this one plant species is to the mintenance of biodiversity.

In fact, a single oak can support up to 534 different species and leads the list of important native trees providing biodiversity in our forests and woodlands.

In Tallamy’s list, The willow is second supporting 456 species followed by cherrry and plum (also 456); birch trees (413); poplar, cottonwood (368); crabapple (311), Maple, box elder (285), Elm (213); pine (203); Hickory (200); Hawthorn (159); spruce (156) …”

If attracting birds and creating a biodiversity of insects, caterpillars, moths and butterflies in your garden is important to you, I urge you to get Tallamy’s book and use it as a bible for creating your backyard landscape design.

Blessed with mature trees in our yard

When we bought our home here in southern Ontario some 25 years ago, my wife and I were blessed with several large trees on the property, including two lovely locust trees, a large linden and Austrian pine in the backyard and two large maples in the front yard of the property. Since then, more trees big and small (at last count 28) have joined the originals to help form the foundation of our woodland.

The understorey: Where the (real) fun starts

The middle layer is the one that can really shine in the woodland.

This is where you can introduce a myriad of flowering trees. Think flowering dogwoods, both the native variety (Cornus Florida) with a multiple of hybrids or the prolific Kousa Dogwoods that flower later in the season after the leaves appear on the branches. A combination of the two gives you a magnificent show from early spring into summer. Then, if you have room, intermingle a couple of Redbuds (link to my post on Redbuds) or Serviceberries between the dogwoods. Their ethereal flowers are absolute showstoppers in any garden big or small.

And, if that’s not enough, how about a couple of azaleas growing beneath the Dogwoods, Serviceberries and Redbuds. That’s a showstopper.

These are just a few ideas to think about while you contemplate your Woodland. Future posts will delve a little deeper into the different layers, so stay tuned. For example here is a post on three of my favourite groundcovers. Here is another post on a favourite groundcover for a hot dry location. This post looks into moss as a ground cover and plants that create a similar experience as moss in the garden.

I would love to hear some of your planting ideas for your top two layers your Woodlands. Share them with us below in the comment section.

This page contains affiliate links. I try to only endorse products I have either used, have complete confidence in, or have experience with the manufacturer. Thank you for your support.

Carolinian Canada is a diamond in the heart of Southern Ontario

Carolinian Canada is a sweep of land that extends from Toronto to Lake Erie and down through Windsor to Lake Huron. Its diversity of flora and fauna is unmatched anywhere else in Canada. The Carolinian forest also stretches through much of Eastern United States.

A Woodland Gardener’s journey of discovery

I am not sure when my love of gardening took root.

Two factors, however, played a major role in both my love of gardening and how I came to appreciate a Woodland Garden over, let’s say, a more formal style of gardening.

I was in my mid-twenties and working at a large weekly newspaper in the the metro Toronto area when I got my first real taste of the joy of gardening. I remember interviewing the president of the local garden club, touring his lovely suburban garden and sharing in his excitement for the diversity of flowers, shrubs and trees that grew in his garden. It definitely was not a Woodland garden but it left a big impression.

At the same time I was getting more and more involved in nature photography and my weekends were often spent wandering the local forests looking for wildflowers and other subjects that caught my eye. As my photographic knowledge grew, so did my appreciation for the more wild areas where I lived. Photographing trilliums, dog-toothed violets, hepatica, bloodroot and the ultimate photographic subject – native lady slipper orchids – became a spring ritual. In the summer months, our focus shifted to reptiles and mammals that seemed abundant in the ponds, rivers and forests that my photographic friends and I explored.

Fall, of course, was the magical time for Ontario photographers and nature lovers when the forests were blanketed with the spectacular reds, oranges, yellows and ambers of the season.

Carolinian Canada is an important ecosystem in Ontario that needs Woodland gardener’s assistance.

What I didn’t know at the time was that the driving force behind all of this was the fact I lived in one of the most beautiful, diverse and fascinating areas in Ontario. At the time it was just the forest. I later learned that it wasn’t “just a forest,” it was a very specific type of forest that made it special.

It was the Carolinian Canada forest.

Carolinian Canada is a rare gem

It’s a stretch of forest that sweeps from Lake Erie to Toronto, just kisses Guelph and Kitchener-Waterloo before heading up to Windsor and Lake Huron. Carolinian Canada boasts a diversity unmatched anywhere else in the country. From its unusual variety of trees to its rare plants, birds, mammals, insects, amphibians and reptiles, Carolinian Canada is certainly a nature lovers dream.

The Carolinian Canada forest is characterized by the predominance of deciduous trees and actually stretches well into the United States from the Carolinas, through the Virginias, Kentucky, Tennessee, Maryland, Delaware, Pennsylvania, parts of Ohio and New York state to name just a few. In the U.S., the Carolinian zone is commonly called the “Eastern Deciduous forest.”

Yellow lady slippers

Carolinian Canada includes primarily the gardening zones 6-7 and share many of the same fauna and flora.

Trees of note include hickory, oak, walnut, and the tallest of the lot, the tulip tree. In addition, there are the understory trees featuring native dogwood (cornus florida) and the pawpaw tree with it’s large, exotic fruit that tastes very similar to a mango.

In Southern Ontario the presence of the Great Lakes and their moderating influence creates the environment necessary to boast the longest frost-free seasons and the mildest winters of any region in the province.

The outstanding features of the Carolinian Forests in Ontario is also its downfall. The climate, fertile soils and proximity to large fresh-water lakes means that Carolinian Canada is highly developed and includes some of Canada’s most populated cities, intensively farmed agricultural areas and heavy industrialized locations. All this intensive settlement, industrialization and agriculture has led to significant habitat loss and fragmentation, leaving scattered and disconnected parcels of land left to carry on the natural ecology that makes up this important ecosystem.

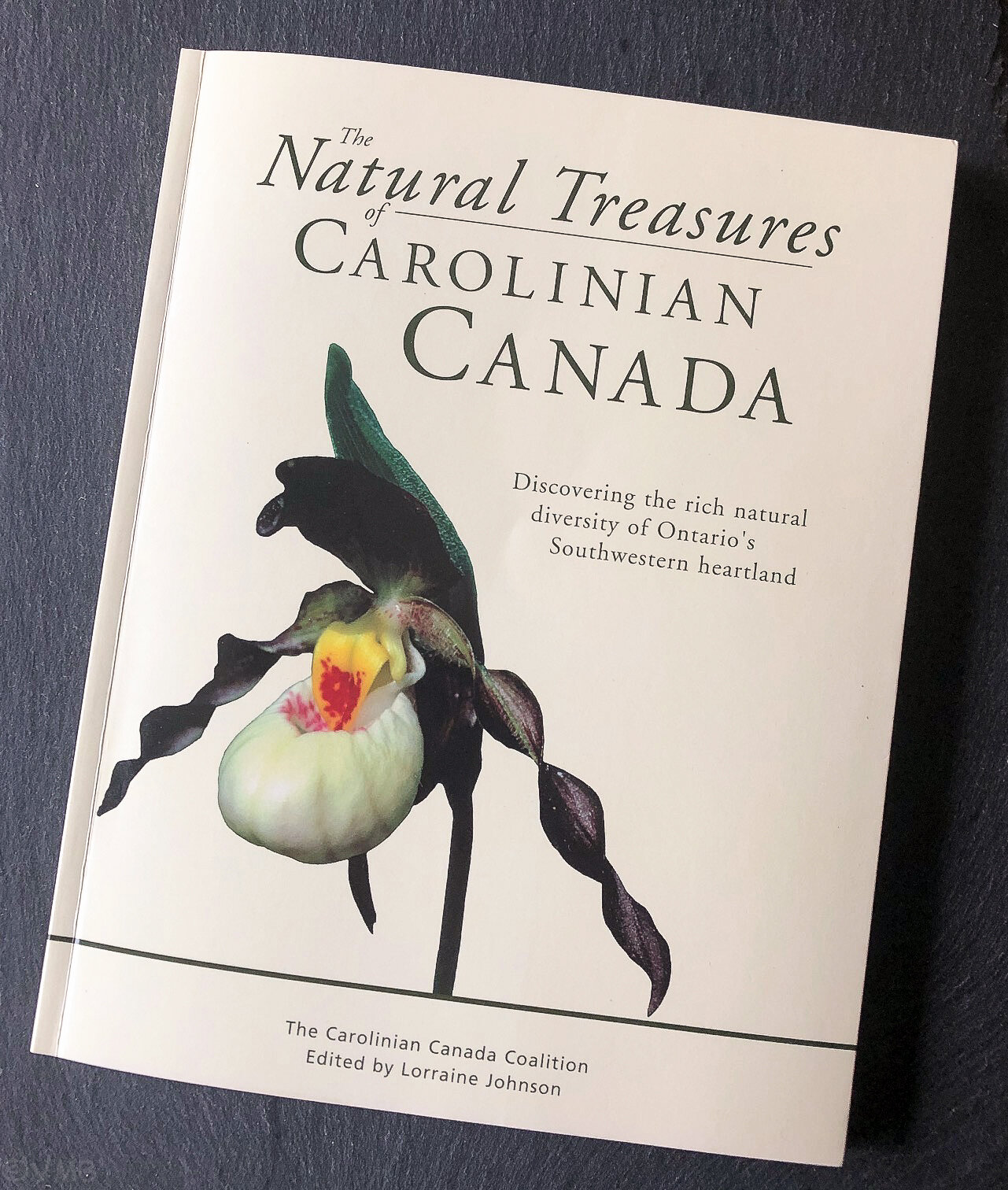

The Natural Treasures of Carolinian Canada, published by James Lorimer& Company Ltd., is an outstanding resource for Woodland Gardeners who want to explore the Carolinian Canada forest more fully.

I was fortunate enough to be awarded this book as part of being recognized by the Hamilton Conservation Authority Watershed Stewardship Program for the efforts my wife and I have made on our property to care for the land in such a way to maintain a healthy state for today and for future generations. More on that in a later blog.

I took the time this winter to study this almost 150-page book. The book is edited by native plant expert Lorraine Johnson with individual chapters written by experts including naturalists and scientists working at World Wildlife Fund, the Nature Conservancy of Canada, The Royal Ontario Museum as well as many universities and government natural resources ministries.

It explores in great depth the various ecosystems within Carolinian Canada from the plants to the forests, the prairie peninsula and the wetlands. In chapter two, the authors focus on the fauna everything from badgers (yes there are badgers in Norfolk county) and flying squirrels to the birds, butterflies, amphibians and reptiles.

Finally, the authors turn their attention on stewardship and how humans can reshape the land and ecosystem they have played a major role in destroying, or at least bringing to the edge of distinction. These are important chapters; ones that, as Woodland gardeners, we have the opportunity to play a vital role in reshaping.

Woodland gardeners have a say in Carolinian Canada’s future

Whether we garden in a sensitive and highly threatened ecosystem like Carolinian Canada, a prairie grassland, the rolling hills of the mid-west or a desert landscape, all gardeners, but especially Woodland gardeners have the ability to influence the future of these important places.

Wherever you live and garden, there are organizations that work to protect the natural environment. Gardeners fortunate enough to live in Southern Ontario can take advantage of the vast resources and expertise that exists at Carolinian Canada, whose mission is to “advance a collaborative conservation strategy for healthy ecosystems in Ontario’s Carolinian Life Zone.”

The organization’s diverse network works to advance a “strategic ‘Big Picture’ vision for healthy landscapes and a green future in Canada’s deep south.”

Its website (see link above) states that since 1984, Carolinian Canada Coalition has been a leading ecoregional group, bringing together thousands of people and groups who care for the unique habitat network, and to support thriving wild and human communities in harmony for generations.

For our part, my wife and I do our best to plant native trees, shrubs and flowers, but we do not get too hung up on planting only natives. We try to plant fruit- and nut-bearing trees and plants to help local fauna. We put up bird houses on the property, have both above-ground bird baths and on-ground water sources for birds, amphibians and mammals and have a large debris pile to give mammals, reptiles and insects places to harbour over the winter. We have removed all the grass from our front yard and most of it from the back yard. (What’s left in the back yard is a combination of moss, wildflowers with a little lawn mixed in.) Chemicals are rarely used and branches, leaves and garden debris never leave the site.

Not everyone has the space or are willing to keep all the leaves and garden debris on-site, but if we all make an effort to do the best we can, we can play a significant role connecting these fragmented wilder areas and provide corridors for birds, mammals and flora to prosper even in some of the most built-up areas imaginable.

This concept is what Irish garden designer, naturalist and renowned author Mary Reynolds promotes with her gardening-inspired movement We Are the Ark and her book Garden Awakening, which was reviewed on this site in the previous blog.

Woodland gardeners have been building ARKs (Acts of Restorative Kindness) for years. Now we have a reason to celebrate our efforts and work to convince others to join us in celebrating the natural forests where we live.

More links to my articles on native plants

Why picking native wildflowers is wrong

Serviceberry the perfect native tree for the garden

The Mayapple: Native plant worth exploring

Three spring native wildflowers for the garden

A western source for native plants

Native plants source in Ontario

The Eastern columbine native plant for spring

Three native understory trees for Carolinian zone gardeners

Ecological gardening and native plants

Eastern White Pine is for the birds

Native viburnums are ideal to attract birds

The Carolinian Zone in Canada and the United States

Dogwoods for the woodland wildlife garden

Bringing Nature Home by Douglas Tellamy

A little Love for the Black-Eyed Susan

Native moss in our gardens

This page contains affiliate links. If you purchase a product through one of them, I will receive at commission (at no additional cost to you)I only endorse products I use, have complete confidence in or have experience with the manufacturer.

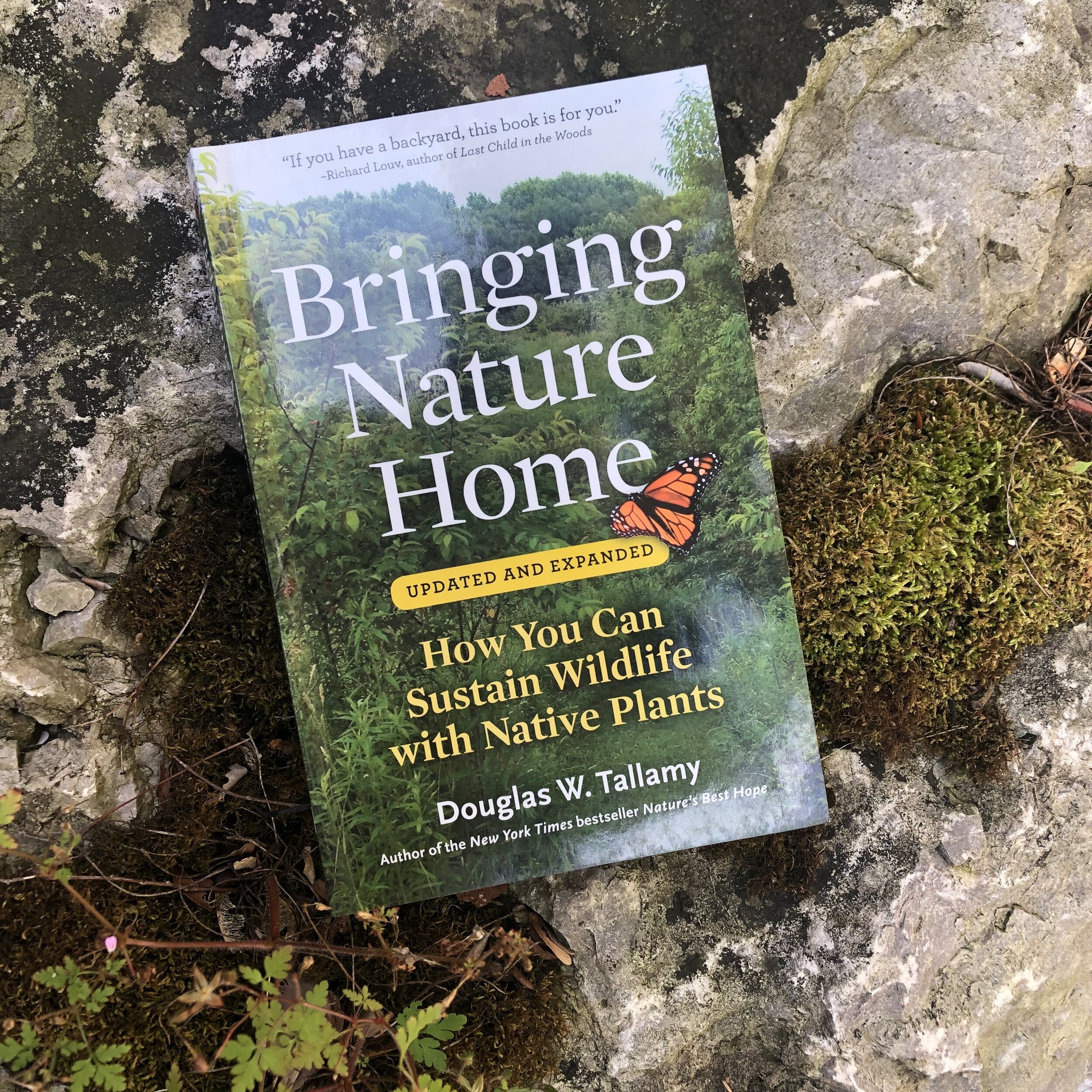

Going Native: Saving nature one backyard at a time

Bringing Nature Home is a book every gardener needs to read. The book is a rich resource for woodland gardeners looking to better understand the importance of native plants in our environment and the dangers of using exotics. It is a comprehensive blueprint for how gardeners can use native plants to sustain wildlife

Bringing Nature Home: Sustaining wildlife with Native Plants

There is plenty to be optimistic about in Douglas Tallamy’s book, Bringing Nature Home and it all begins with the importance of planting native plants, trees and shrubs in our gardens.

But finding this optimism is not easy.

For my extensive article on why using native plants in your garden is important, go here.

Tallamy tells the truth and it’s a truth that will make most gardeners very uncomfortable about what we’ve planted in the past and what is now happily growing in our gardens right now.

The must-have ornamentals, the pest-resistant perennials and the trees and shrubs we probably never suspected were problematic in the landscape are creating the conditions for the slow but steady decline not only of native plants but the entire ecosystem that depend on them for survival.

Scary stuff for sure, but critical reading for anyone who cares about the environment and what awaits future generations.

Remember, I said there’s lots to be optimistic about in the book. It’s important to note that the its full title is “Bringing Nature Home. How You Can Sustain Wildlife with Native Plants.” The book proves to be a rich resource for combating the incredible damage we have inflicted on our land and the wilder places that surround us.

For more on the importance of oak trees in our garden and natural landscapes take a few moments to check out my other posts on Oak trees:

This recent book release is an updated and expanded version of the same book that was first published in 2007.

Tallamy goes to great lengths in the opening chapters to explain the enormous problems we face following the slow and steady introductions of exotic, alien plants, pests and disease brought to North America – sometimes by mistake but often through the nursery trade. The problem these exotic ornamentals bring are twofold: One, they fail to deliver the same nutritional benefits to our insects as native plants, and; Two: many of these alien plants have displaced once dominant native plants in our gardens and in the wild.

The result is devastating to a host of native insects, reptiles, animals and birds.

How we can restore native habitats

Tallamy concludes that all the points in his book converge in a common theme: “we humans have disrupted natural habitats in so many ways that the future of our nation’s biodiversity is dim unless we start to share the places in which we live – our cities and, to an even greater extent, our suburbs – with the plants and animals that evolved there. Because life is fuelled by the energy captured by the sun by plants, it will be the plants that we use in our gardens that determine what nature will be like 10, 20, and 50 years from now.”

He goes on to explain that if gardeners continue to “landscape predominantly with alien plants that are toxic to insects…. We may witness extinction on a scale that exceeds” anything ever experienced on this earth.

Tallamy recognizes that it is probably too late to turn back time and completely eliminate the alien plants either from our gardens or from wild places, but it’s not too late to use our gardens – big or small – to create islands of native-plant sanctuaries to give native fauna a chance to recover. One small island in suburbia will not solve the problem, so Tallamy encourages readers to recruit neighbours, maybe even entire neighbourhoods to transition from exotic to native plantings.

He goes into great detail to help readers recognize the benefits of using natives over exotics, even listing the best native trees and plants to use in the garden (broken down by zones). Not only does he list the trees and plants, but he includes scientific numbers on how many Lepidoptera species benefit from individual trees. For example, Oak trees rank first supporting 534 species, willows are second supporting 456, followed by Cherry/plum at 456 and birch at 413.

Tallamy speaks with great authority. He is a professor in the Department of Entomology and Wildlife Ecology at the University of Delaware, where he has authored 97 research publications and has taught insect related courses for more than 40 years. Using this knowledge, he provides valuable information on every insect and spider you might come across in the garden.

It would be easy to think this is a book for environmentalists, but it really is a book for gardeners. There are even sketches on how to use native plants in the garden to benefit our native wildlife.

For woodland gardeners, many of whom already recognize the importance of using native trees, shrubs and plants, the book helps to validate what you are already doing. For those who have not given a lot of thought to the potential damage exotics create in the environment, the book will get you to question many of your existing beliefs and garden aesthetics.

No matter where you stand, this book – not unlike Mary Reynolds’ book “The Garden Awakening: Designs to Nurture Our Land and Ourselves – will force you to rethink how you garden. Together, they form a powerful voice calling for major changes to suburban gardens away from landscapes dominated by large swaths of non-native grass and exotics, to mass planting of native trees, shrubs, plants and grasses.

It’s a voice gardeners and garden designers need to listen to, need to act on and need to convince others to act on.

Our children deserve a chance to enjoy the birds, butterflies and insects as much as we did growing up.

In addition to Mary Reynold’s book, The Garden Awakening” mentioned above, I have written a number of posts that relate to the subject of native plants. Here are just a few readers may want to explore further. Woodland Nurseries gardeners need to know about . So You Got Perfect Grass: That Don’t Impress me much.

This beautiful, 358-page soft-cover book was provided to me by the good folks at Timber Press for review. It is an outstanding resource for any gardener intent on creating a healthy backyard habitat for birds, butterflies, insects and mammals. The New York Times best seller has been praised by all who take the time to explore it. Writes The New York Tmes: “Tallamy’s message is loud and clear: gardeners could slow the rate of extinction by planting natives in their yards.”

William Cullinar, Director of Horticultural Research for the New England Wild Flower Society, writes “We all hear that insects and animals depend on plants, but in Bringing Nature Home, Douglas Tallamy presents a powerful and compelling illustration of how the choices we make as gardeners can profoundly impact the diversity of life in our yards, towns and on our planet. This important work should be required reading for anyone who ever put shovel to earth.

• If you are considering creating a meadow in your front or backyard, be sure to check out The Making of a Meadow post for a landscape designer’s take on making a meadow in her own front yard.

More links to my articles on native plants

Why picking native wildflowers is wrong

Serviceberry the perfect native tree for the garden

The Mayapple: Native plant worth exploring

Three spring native wildflowers for the garden

A western source for native plants

Native plants source in Ontario

The Eastern columbine native plant for spring

Three native understory trees for Carolinian zone gardeners

Ecological gardening and native plants

Eastern White Pine is for the birds

Native viburnums are ideal to attract birds

The Carolinian Zone in Canada and the United States

Dogwoods for the woodland wildlife garden

Bringing Nature Home by Douglas Tellamy

A little Love for the Black-Eyed Susan

Native moss in our gardens