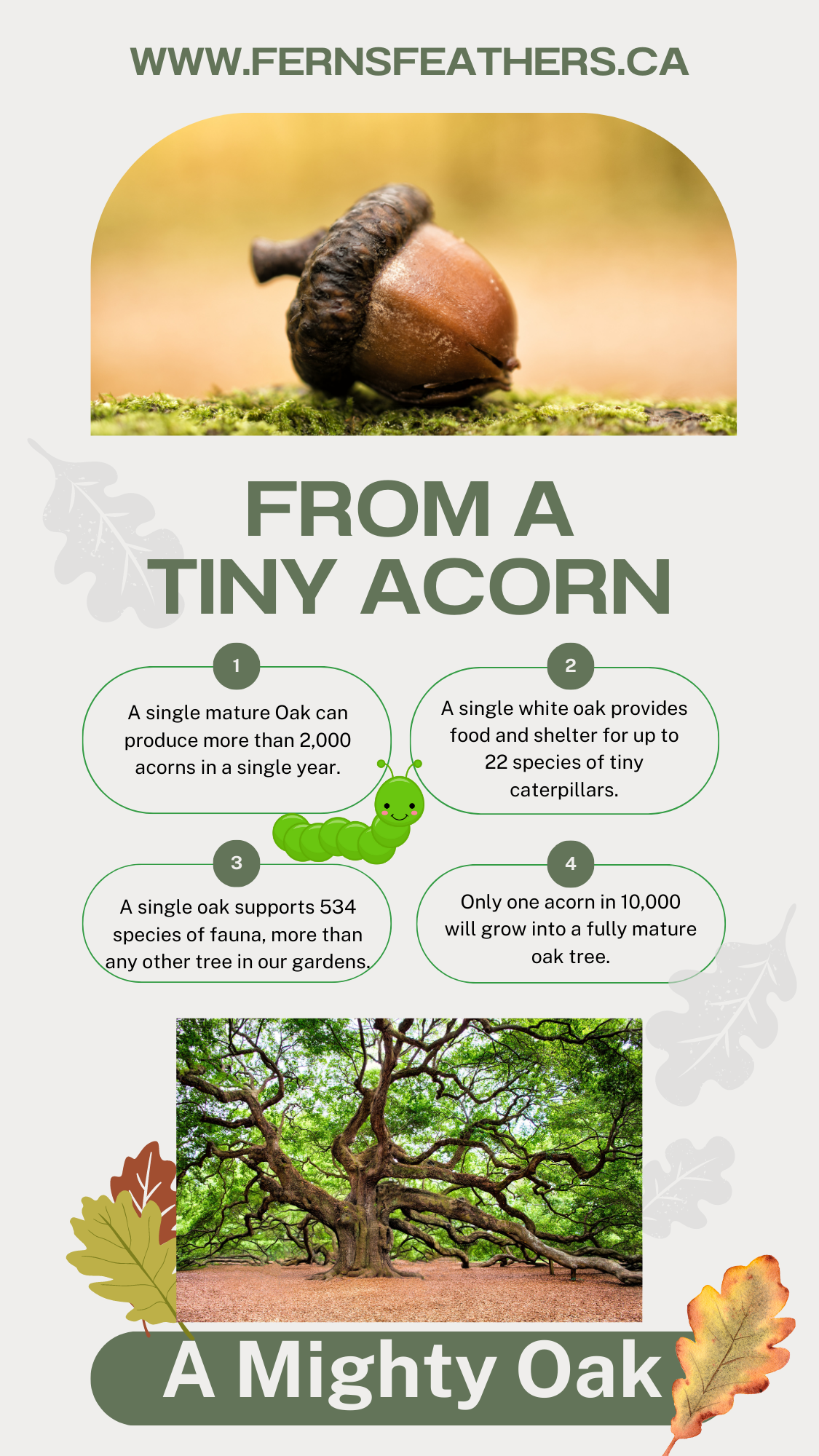

From a tiny acorn, a mighty Oak grows

Our mighty oaks have humble roots

“Large streams from little fountains flow, Tall oaks from little acorns grow”

– D. Everett in The Columbian Orator, 1797

Our neighbour’s giant oak tree crashed to the ground several years ago. I guess it had lived its life to the fullest and was now offering itself up to the earth.

But, its work was not finished.

All around it, in our yard and, I imagine, many yards in the neighbourhood, this giant oak’s offspring had already begun their own lifelong journeys.

All from a little acorn that had fallen from the old oak tree and likely forgotten by a resident squirrel after it buried the acorn in the ground with the hope of using it for a meal in the cold of winter.

Just in case you were not aware, the seed of an oak tree, the “nut,” is called an acorn.

It is believed that the average 100-year-old oak tree will produce as many as 2,200 acorns per year. That number will go up significantly during high production years that can occur every four to ten years.

I often find small oak saplings growing on our property. In spring, I move them to safer areas to grow in the back of the garden where they are safe and have a much better chance of growing to maturity. Often, during the move, remnants of the woody acorn shell remains on the small roots, a stark reminder of the the saplings’ origins.

If you are trying to decide whether or not to plant an Oak tree in your yard, The Nature of Oaks will certainly help you make that decision. This valuable book highlights the incredible benefits of these important trees.

For more on the importance of oak trees in our garden and natural landscapes take a few moments to check out my other posts on Oak trees:

It should not be forgotten that of the more than 2,000 acorns per year that fall from a mature oak, very few of those seeds grow into oak trees themselves. In fact, it is estimated that only one acorn in 10,000 will grow up to be an oak tree.

Some species of oaks bear acorns yearly, while others bear every two years.

The remainder provide food and even shelter for much of the wildlife in our yards.

It’s hard to believe how hard oaks work for the earth’s creatures.

How important are oaks to our wildlife?

In his highly acclaimed book Bringing Nature Home, How You Can Sustain Wildlife with Native Plants, Douglas Tallamy spells out clearly the vital role Oaks play in the natural environment and how important they are to include in our gardens.

He writes: In a study in Illinoise, John Nill and Robert Marquis (2003) found that a singe white oak tree can provide food and shelter for as many as 22 species of tiny leaf-tying and leaf-folding caterpillars, insects most people never notice on their walks in the woods.”

And that is just a tiny fraction of the fauna in your garden that depend on a single oak tree. In fact, the mighty oak supports 534 species of fauna, more than any other tree we can plant in our gardens.

It is followed by the willows, cherries and plums, in importance to fauna. All good choices when it comes to deciding what tree to plant in your garden.

If the Oak’s importance to wildlife is not enough, consider that of the 400 species of Oak, North America boasts 90 different species with 75-80 in the United States and 10 in Canada.

How long do Oaks usually live?

Oak trees traditionally live for hundreds of years. There’s a good chance your children will be watching the tree enter middle age long after you’re gone.

In Ontario and northeastern United States, that white oak you plant will grow more than 35 metres (that’s more than 114 feet) tall, can live for several hundred years and produce thousands of acorns every year to feed deer, squirrels (including flying, red and gray), chipmunks, wild turkeys, crows, rabbits, bears, mice, opossums, blue jays, quail, raccoons and even wood ducks just to name a few.

As Tallamy points out: “The value of oaks for supporting both vertebrate and invertebrate wildlife cannot be overstated.”

He explains that oaks along with hickories, walnuts and American beech, have stepped up to the plate following the demise of the American chestnut in supplying nut forage for various forms of fauna.

In addition, oaks – both living and dead – provide nesting cavities for our backyard birds ranging from chickadees, wrens, woodpeckers, owls and even bluebirds.

The tree species real genius, however, is what we alluded to earlier, and that is the astounding number of insect herbivores that oaks support in the forest ecosystem.

“From this perspective, oaks are the quintessential wildlife plants: no other plant genus supports more species of Lepidoptera, thus providing more types of bird food, than the mighty oak,” Tallamy writes.

(If you are wondering what a Lepidoptera is: They represent an order of about 180,000 species in 126 families and 46 superfamilies of insects that includes butterflies and moths. It is one of the most widespread and widely recognizable insect order in the world, and your average oak is full of them.)

And all from the tiny acorn.