Sumac: First signs of fall in the garden

Staghorn Sumac is an excellent addition to the garden both to add architectural interest and provide a food source for birds and animals.

Important food source for birds and other wildlife

It’s early October and the native Sumac is already lighting up the roadsides and welcoming the first signs of fall in the woodland garden.

Along roadsides and escarpments, where this fast-growing native shrub or small tree (grows to about 30-feet high) gets plenty of sun, Sumac lights up with brilliant oranges, yellows and reds.

It’s often the first plant nature photographers focus on when in search of early colour in the fall landscape, and it’s a perfect addition to the woodland garden. Sumac has compound, serrated leaves that are a bright green in summer before taking on its fall cloak.

How did Sumac get its name?

There is no missing the velvety bark on the branches that cover Staghorn Sumac. This velvet resembles the velvet that covers the antlers of male deer (stags) throughout the summer, earning Sumac the name “Staghorn”.

There are more than 30 varieties of Sumac in North America with more native varieties in Europe, Africa and Asia.

Is Sumac a food source for birds and other wildlife?

Not only is Staghorn Sumac (Rhus typhina) an incredibly colourful addition to the woodland, its fall berries, that grow in large clusters atop the shrub’s branches, are also a very important source of high-value food for birds especially migrating birds.

Staghorn Sumac puts out small greenish-yellow flowers that attract pollinators. They grow in the shape of a cone in spring and become the reddish-haired fruit clusters as summer turns to fall.

These hearty fruit clusters, that often remain on the plant well into winter, are vital resources for hundreds of bird species including our backyard favourites like Cardinals, Gray Catbird and a host of woodpeckers ranging from the impressive Pileated to the small Downy and larger Hairy woodpeckers. Add to that list the American Robin together with other thrush species. In a more wooded natural area, don’t be surprised if it attracts Ruffed Grouse and wild Turkeys.

As an added bonus these plants are deer resistant.

Staghorn sumac is dioecious, meaning that it has individually male and female plants.

These shrubs/small trees are extremely hardy, and are both drought and salt tolerant. They prefer a sunny location and dry to moist soil and will not tolerate shade or wet soil. Use these fast growers as an erosion control plant if you have problematic areas.

Where I live, The Niagara Escarpment is the dominant geological feature that cuts through the landscape. The Staghorn Sumac lights up the many cuts through the escarpment and turns the roadsides into sparkling jewels at certain times of day.

Staghorn Sumac is native to the more southern half of Ontario, and eastward to the Maritimes.

Sumac species include both evergreen and deciduous types. They generally spread by suckering, which allows them to quickly form small thickets, but can also make the plants overly aggressive in some circumstances.

There are usually several varieties available at nurseries, but this attractive native is probably all you will need.

Other forms of Sumac

At one of my local nurseries there are three Sumacs listed including the Staghorn Sumac. The others are Fragrant Sumac, and a dwarf variety of fragrant sumac called fragrant gro low Sumac as well as Cutleaf Smooth Sumac.

Cutleaf Smooth Sumac (Rhus glabra Laciniata) is a smaller hardy shrub (hardiness zone: 2B) with finely cut tropical-looking leaves that add texture to the garden. Grown primarily for its ornamental fruit, and its open multi-stemmed upright spreading habit. It lends an extremely fine and delicate texture to the landscape and can be used as a effective accent feature. Click on the link for more information on the Cutleaf Smooth Sumac.

Gro Low Sumac is described as low growing and compact shrub with interesting foliage turning brilliant colors in fall and bright yellow flowers in spring. Makes an excellent ground cover as it tends to sucker, filling in areas quickly. Does well in shade. Click on the link for images and more information on the Gro Low Sumac.

Fragrant Sumac is described as a rugged and durable medium-sized shrub with interesting foliage turning brilliant colors in fall and bright yellow flowers in spring. Tends to sucker, forming a dense spreading mass, attractive for a garden background or for naturalizing, good in shade.

How to grow and care for native Asters

Three native asters for the natural garden that provide late-season resources for pollinators and add a beautiful textural feel into the fall.

Three native asters: Ideal plants for our natural gardens

Our native asters are stealing the show in the meadows and open woodlands around our home reminding us that, if we are not already growing them in our gardens, its time to plant them for next fall.

In our garden the wood asters have made an appearance along with the Woodland Sunflowers, goldenrod and Black-eyed Susans across the back area of our garden.

Do Wood Asters attract pollinators?

The White Wood Asters (Eurybia divaricata), also known as Heart-Leaved Aster, are delicate whitish-blue flowers that add an airy feel to the garden and the perfect excuse for the small pollinators – native sweat bees and small butterflies as well as other insects – to stop by and enjoy a late summer harvest.

New England Asters growing in a naturalistic setting. What some people may think of as a weed, are actually beautiful native wildflowers that are vital to native bees and wildlife.

Embrace these plants and the somewhat messy look they sometimes bring to your garden and focus on the wildlife that find your garden aesthetics just perfect – because it is perfect – for them.

These perennial plants grow between 30 to 90 centimetres (12-35 inches) tall, with heart shaped leaves on the lower parts of the plant and changing to more elongated and deeply serrated on the upper reaches of the plant.

For more information on native plants, check out my earlier articles: 35 native wildflowers and Why we need to grow native plants.

If you are thinking about growing your own meadow garden, be sure to check out garden designer Angela den Hoed’s meadow garden and her five favourite plants for the meadow garden.

White wood asters, New England asters combine beautifully with goldenrod.

How to grow Wood Asters

These are a form of shade-loving asters that can be found growing naturally in dry, organic-rich woodlands and on the edges of forest areas in part shade.

Ours are growing happily on the edge of our ancient crabapple trees, where conditions seem almost ideal for them.

Although these asters will tolerate full shade or sun, they are happiest in part shade. Their beautiful, yet delicate branching clusters of pale blue flowers give a nice airy feel to the garden as well as providing a good source of nectar and pollination for both bees and butterflies.

Hardiness Zone: 3-7

Light: Part shade to full sun

Moisture: Tolerates dry soil, shade to part shade neutral to slightly acidic conditions.

Soil: clay loam to sandy loam, organic

Mature Height: 3-feet-high

Growth: Vigorous or aggressive, even in dry shade.

Propagation: Can be started from seed (seeds mature in late fall), by dividing clumps in early spring or allowed to spread entirely on its own.

This informative infographic designed by Justin Lewis shows the value of the New England Aster.

Are Wood Asters a threatened species?

The Wood Asters’ range is quite broad despite its extremely limited range in Canada where it is confined to a small number of sites in the Niagara region and in more southern areas as well as a few woodlots in southwestern Quebec.

In the United States the Wood Aster ranges from New England south into Georgia and Alabama.

In Ontario, according to the government’s website, the Wood Aster has been considered a threatened species since before 2008, meaning that the plants are not yet endangered but are on that path if action is not taken.

All the more reason to plant some of these delicate little flowers in your garden.

The government website adds these quick facts about the Wood Aster:

White wood aster seeds are dispersed by the wind but are generally not carried for long distances; this may account for its low colonization rate and restricted range

White wood aster is also known as the Heart-leaved aster because of the shape of its lower leaves

The flowers of White wood aster are attractive to butterflies and it is the host plant for Pearly crescents, a common North American butterfly

Right on cue our plants began to flower in mid September with their yellow and purple florets surrounded by the white petals.

The White Wood Aster likes to grow in colonies where it spreads via underground roots.

The plant’s decline in Ontario and Quebec is attributed to a number of factors, including habitat loss as well as competition from increased recreational activities ie: trampling by hikers, bikers and ATVs. Deer grazing and competition from invasive garlic mustard are also putting stresses on the plant in natural settings.

New England Asters in a naturalized setting growing among native grasses.

New England Aster: Dominant flower along roadsides and open fields

New England Asters are happy growing in part shade to full sun in our gardens and naturalized areas along our roadside and open meadows.

Plant them in sandy loam and these late summer/fall bloomers will reach heights of 5 feet with impressive, purple blooms sporting orange centres.

By cutting back the plant in mid-summer (Chelsea Chop: Link to Fine Gardening article), it’s possible to keep the plant a little more manageable throughout the fall.

New England Aster, like all late-blooming perennials, is a critical source of late-season nourishment for pollinators. If you have ever observed the plant in late summer, its attraction to native bees, butterflies and other insects is noteworthy.

New England Aster is distinguished from Smooth Blue Aster by its hairy stem.

Good companions plantings for New England Aster

If you have a meadow garden, consider pairing this aster with Goldenrod, Oxeye daisy, Woodland sunflower and late-season grasses.

Large Leaved Aster is another winner in the woodland

Large Leaved Aster (Eurybia macrophylla) grows in part shade to full sun in zones 3 to 9. It prefers a sandy loam with medium moisture and will grow to about 4 feet tall.

This is another shade-tolerant aster that can work in a woodland-style garden. Consider planting them on the edges or in small clearings where they can benefit from some sunny periods.

The plant’s pale blue blooms are secondary to the 4-8 inch heart-shaped basal leaves that form almost a ground-cover-like carpet.

In conclusion: Asters are important in our landscapes and natural areas

It’s easy to disregard the importance of Asters in our landscapes. Many gardeners focused on aesthetic, non-native gardens would consider the plants weeds and eliminate them as soon as they seem these perennials encroaching on their gardens.

This approach is one of the main reasons asters are disappearing in gardens and open meadows throughout North America and Europe.

In turn, our native bees, butterflies, caterpillars and other insect numbers are falling and threatening the health of our birds that depend on these insects to survive and feed their young.

As woodland or naturalistic gardeners, it is rewarding to know that we are doing our small part to restore the ecosystem and protect plants that are either threatened or spiralling downward.

Embrace these plants and the somewhat messy look they sometimes bring to your garden and focus on the wildlife that find your garden aesthetics just perfect – because they are perfect.

Purple pearl-like berries make Beautyberry a showstopper in native gardens

The American Beautyberry is a fall standout in the woodland garden with it pearl-like magenta berries. The native plant attracts bees and butterflies with its late summer bloom of delicate pink and white flowers, followed by spectacular late summer fruit that persists through winter.

The bright berries that look more like clusters of elegant purple pearls are the prize at the end of summer that makes the American beautyberry bush a must for native gardeners.

The fact that these stunning, glossy, iridescent-magenta fruit, which hug the branches at leaf axils throughout fall and winter, are favourite food sources for migrating birds makes these shrubs among the most prized of plants for gardeners looking for a native plant that turns the sad end of summer into a celebration.

This bumblebee became covered in pollen after working the beautyberry flowers. The flowers will eventually turn into the beautful pearl-like purple berries.

Beautyberries attract bees and butterflies

In mid summer, when the flowers are in bloom, the shrubs also attract native bees and butterflies.

What more can a native gardener ask for?

How about an attractive, arching shrub at home in a woodland understory or at the edge of a forest where it gets full sun to part sun,

Where can you grow Beautyberries?

American beautyberries (Callicarpa americana) are found in warmer parts of Canada and throughout the United States from Virginia to Arkansas and south to Florida and into Texas. They are generally hardy from Zones 6-1.

If you are looking for it growing naturally, look in woodlands, moist thickets and other wet areas including low rich bottomlands, swamp edges and pine woods.

If you are looking for more information on growing native flowers, you might be interested in going to my comprehensive article: Why we should use native plants in our gardens.

Other shrubs known for their berry production include a long list of viburnums. If you are looking to add more berry producers to your garden, check out my comprehensive post on Seven Viburnums that attract birds to your garden. In addition to Viburnums there are many plants, shrubs and small trees to consider. My post Best plants and shrubs to feed birds naturally and save money will help get you thinking about using plants and shrubs as natural bird feeders.

Are Beautyberries low maintenance?

If you are growing Beautyberry in your garden, you’ll be happy to know it is a low-maintenance shrub that is happy enough in moderately moist soil in part shade. Beautyberries grow in moist, rich soils as well as sandy soils, sandy loam and even clay-based soil.

Beautyberries boast spectacular, magenta fruit born in clusters on arching branches that can remain on the shrub into winter.

Is my Beautyberry dead?

Don’t be surprised in late spring if there is no sign of life in your Beautyberry. These shrubs are slow to bud out in the spring, but the American beautyberry can reach an average of 3-5 feet tall and often about the same width. In good soil, don’t be surprised if it reaches up to 9 feet high with a similar width. it can be cut down regularly to keep it in check if necessary.

During the summer, the shrub with its arching branches and ovate to elliptic, leaves. that grow in pairs or in threes up to nine inches long, are fairly inconspicuous blending in with other shrubs in the garden border or filling in under larger mid-canopy trees.

If used as a specimen, it can be an elegant understory shrub with a naturally loose and graceful arching form.

Plant it as a mid-size understory shrub at the edge of the landscape where it can get partial sunlight during the day, preferably in morning or late afternoon.

In late summer – mid august in our area – small, pink flowers appear in dense clusters at the base of the leaves. These delicate clusters of flowers are easily overlooked.

Gardeners familiar with the shrub know however, that the more flowers they have on their beautyberries the more berries they can look forward to in late summer into fall.

Flower buds on a Beautyberry bush getting set to emerge and eventually turn into the purple pearl-like fruit that is attractive to a variety of birds including robins, cardinals and mockingbirds.

The fruit or berries can be rose pink or lavender pink and about 1/4 inch long. The extremely showy clusters cling to the branches through the fall and into winter if the birds and garden mammals don’t get to them first.

Do Beautyberries have good fall colour?

Fall is really the time the shrub comes into its own as the leaves slowly turn yellow revealing the incredibly showy clusters of glossy fruit. The combination of the yellow leaves and magenta fruit is a combination that you will want to ensure is front and centre in the garden.

What birds eat the fruit of Beautyberry?

You can count on American robins, cardinals, finches, towhees and even mockingbirds visiting your shrub in search of the pearlescent, purple fruit. Foxes, raccoons, chipmunks and squirrels will also be lining up for the fruit.

Unfortunately, if you live in deer country, don’t be surprised if deer have a little nibble on the shrubs. Our deer have more or less left the plants alone, although there is so much more in the garden they obviously seem to prefer.

Although American Beautyberry shrubs are commercially available, (you may have to look for Callicarpa americana on the tag ) they are relatively easy to propagate from seeds, root cuttings and softwood tip cuttings. If you have a friend with one, take a cutting and get a couple for your garden.

Sophisticated elegance makes Beautyberry a late summer standout

The American Beautyberry shrub is another example of a native plant that is often overlooked by gardeners focusing on massive, showy blooms that dominate the landscape but often fall short once the blooms are spent.

This is not what the Beautyberry is all about. Although these understory shrubs have a certain elegance in the woodland garden with their arching stems, don’t expect them to steal the show during the spring and summer months.

But that’s okay.

There are plenty of flowers, shrubs and flowering trees that can do the heavy lifting in May and June. Gardens need colour and interest in late summer into fall and that’s when the American Beautyberry really delivers. As already discussed, the berries/fruit are the showstoppers, but don’t underestimate the fall foliage. The green and almost lemon-yellow foliage of the Beauty-berry is the perfect contrast to all the reds and burnt orange that tends to dominate the landscape at this time of year.

Not only do Beautyberry carry their weight in fall, but they add much needed winter interest to the landscape with their purple berries popping out of the drab landscape. Imagine watching a cardinal feeding on the colourful fruit and you will know why native woodland gardeners have a special place in their hearts for Callicarpa americana.

Canada Anemone: A native ground cover for woodland garden

Canada Anemone is native ground cover that is ideal for the woodland garden that enjoys a little sun and would benefit from a fast-spreading ground cover with a lovely flower.

Native bees zero in on Canada Anemone

The Canada Anemone (Anemone canadensis) is an ideal choice for a native ground cover that will not only light up the woodland garden in spring when it is in flower, but will also create a lovely textural cover throughout the summer.

I started my little patch from a single plant purchased at the local horticultural society’s annual plant sale. In a few short years, that single plant quickly spread into a good-sized size drift that greets spring with their clear white flowers and yellow centres that can stretch out to be over an inch wide with five sepals held up on long stalks. The flowers stand above the foliage that resembles that of Wild Geranium. New foliage growth emerges a light green giving the plant a fresh look.

The drifts of flowers spread through rhizomes and depending on the soil they either spread quickly in rich, mesic to wet soils, but slower in drier, more well-drained soils. Our soil is definitely dry, but they still spread with great vigour. They can often be seen near sandy dry lakes as well as meadows.

The wildlflower is native to most of eastern North America and is common in the upper midwest and Great Lakes area where I live.

An aerial view shows the flower in both its open and un-open stages as well as the ferny foliage that resembles the foliage of Wild Geranium.

It is a favourite of the early native bees and other pollinators, but our resident rabbits and deer never seem to touch the plants. That could be because they are smart enough to know that all of the parts of the plant are considered toxic.

Making room in our gardens for more and more native plants is vital for the survival of our native fauna, from insects and caterpillars that have developed a relationship with these native plants over centuries, to our native birds that depend on the insects and caterpillars to feed themselves and, even more importantly, their young in the spring when insects are often difficult to find.

They flower about the same time as non-native Epimediums, which enjoy a more shady location. I can see some large drifts of these Canada Anemones growing together with clumps of Epimedium in a part-sun, part shade environment. The ferny foliage would work well with the larger, and more colourful foliage of some Epimedium throughout the summer months, once flowering has ended.

Our little drift will be contributing to more drifts throughout our garden when I transplant some of these original plants to different parts of the garden later this year when the flowering has dried up.

Looking for more information on ground covers? Please check out my other posts on ground covers I use in the woodland garden.

• Bunchberry perfect ground cover for woodland garden

• What is the easiest ground cover to grow?

• Three great ground covers for the woodland garden.

• Creeping thyme as a ground cover

Fall is a good time to transplant them but any time after flowering should be fine, especilly if you are transplanting them in shaded area and give them lots of water to help get them a good start.

These plants may look delicate, but don’t mistake their delicate beauty for weakness, these are a hardy, native ground cover.

Canada Anemones are perennials that grow well in zones 3-8 and reach about a foot tall when in flower.

Like any good ground cover, they are quick to spread and fill in those empty patches in your garden. Plant them in full sun to partial shade for best results and expect blooms from late May into June.

They prefer a wet to medium site but have done well in our dry sandy loam with a layer of mulch to keep the soil cool in the hot sun.

Growing Canada Anemone from seed

Growing these plants from seeds can be difficult.

The seeds actually need double stratification in a cold moist environment before germination and, therefore, could take up to two seasons before plants emerge if seeds are sown directly in the garden in fall.

Best to just get some plants from a friend or a good reputable native plant nursery.

What insects and pollinators are attracted to Canada Anemone

Any native flower that emerges early quickly attracts a host of insect pollinators and the Canada Anemone is no different. Watch for small Carpener Bees, Sweat Bees and Mining Bees visiting the flowers. A host of beetles are also attracted to the flowers, including long-horned and tumbling flower beetles just to name a few.

Obviously, backyard birds will also be checking out the early-blooming flowers for a quick meal of delicious insects.

Making room in our gardens for more and more native plants is vital for the survival of our native fauna, from insects and caterpillars that have developed a relationship with these native plants over centuries, to our native birds that depend on the insects and caterpillars to feed themselves and, even more importantly, their young in the spring when insects are often difficult to find.

Consider replacing non-native ground covers, such as Lilly of the Valley and Periwinkle, with native varieties that perform as well if not better than their non-native counterparts and provide important sources of food for native birds, mammals, reptiles and amphibians.

Another great flower for selective focus

When the Canada Anemone is blooming, it’s time to get out the camera and experiment with a little selective focus. Use a long lens and shoot through the flowers with your lens “opened up” to its widest opening. Now focus on a flower in the distance and let the foreground and background go out of focus.

You could get a similar effect with a macro lens by allowing the flowers in the foreground to go out of focus while focusing on a more distant flower or grouping of flowers.

Flowering Dogwood: The queen of the Woodland garden

The flowering dogwood is an icon of the American landscape with its spectacular spring flowers followed by red berries that birds cannot get enough of as they ripen.

The Flowering Dogwood (Cornus Florida) combines everything a gardener could want in a backyard tree.

If you are lucky enough to live in a region where you can grow this iconic native American flowering tree, whether it’s in your front as a specimen tree or as an understory tree in the backyard woodland or shade garden, you should waste no time sourcing one or even several for your front and back gardens.

In our backyard woodland garden, we have several that fill the garden with showy spring flowers followed by berries in summer and outstanding fall colour.

Its native range is New England south to northern Florida, west to the Mississippi and even beyond. In Canada it finds its range in Southern Ontario’s Carolinian zone.

In the cooler growing zones found in Northeastern U.S. and parts of Canada in zones 5-6 for example, Dogwoods can take more sun than the hotter zones farther south where they are best grown in light to partial shade.

Travelling through the Great Smokey Mountains and along the Blue Ridge Parkway in early spring is perhaps the ideal way to experience magnificent Flowering Dogwood and Redbuds both in full bloom along their still-bare branches.

The Flowering Dogwood grows to about 30-35-feet tall in the wild (often smaller in gardens) with a spread that is about two-thirds or almost equal to its height. It’s a wide spreading mounding tree with branches that can droop right to the ground if left to grow naturally. It likes to grow in partial shade to full sun and prefers moist to dry woodsy loam to a clay-loam.

Flowering Dogwoods flowers from March, April and May followed by clusters of 3-5 red berries (or drupes) from August through October – that are highly favoured by birds and other mammals. It is the queen of the Carolinian forest and and is at home growing in zones 2 through 9. Its mottled bark creates winter interest to the already elegant, horizontal branching of our native tree.

Be sure to check out my extensive article on the Six Best Dogwoods for the Woodland Garden.

More of my posts on Dogwoods

For more information on Dogwoods, please check out my other posts listed here:

Dogwoods: Find the perfect one for your yard

Cornus Kousa: Impressive non-native for the woodland garden

Bunchberry: The ideal native ground cover

Pagoda Dogwood: Small native tree ideal for any garden

Cornus Mas: An elegant addition to the Woodland Garden

The tree’s branching habit of stretching right to the ground suggests that it wants to protect its roots from harsh sun and other root-zone incursions, so it’s a good idea to provide some protection around the tree’s root zone.

A heavy mulch around the root zone will help to hold moisture as well as protect it from direct sun and the damage lawnmowers create when working closely to the tree’s trunk. Do not pile the mulch up around the trunk of the tree. Leave a well stretching several inches to a foot or two around the tree to limit disease and insects.

Our native dogwoods do suffer from disease including Anthracnose, which can take root after a long rainy, cool spring. Anthracnose can attack the flowers and leaves of the tree all summer long and, can eventually kill the tree if it persists for several seasons.

If planted in a location, preferably as an edge-of-the-woods tree, where it gets morning sun to burn off the moisture and dew from the flowers and leaves, Anthracnose is unlikely to be a problem. Ideally, the tree should be planted where it can get afternoon shade to help it escape the extreme heat.

The Flowering Dogwood has dark red to purple fall colour. In spring it makes a great companion for Witchhazel, Redbud and serviceberries as well as the non-native asian relative the Cornus Kousa.

Cherokee Chief is a particularly nice cultivar with a pinkish flowers colour. Some cultivars are available with a darker red colour but the native still stands out best with its white to cream-coloured flowers.

What’s the difference between Cornus Florida and Cornus Kousa?

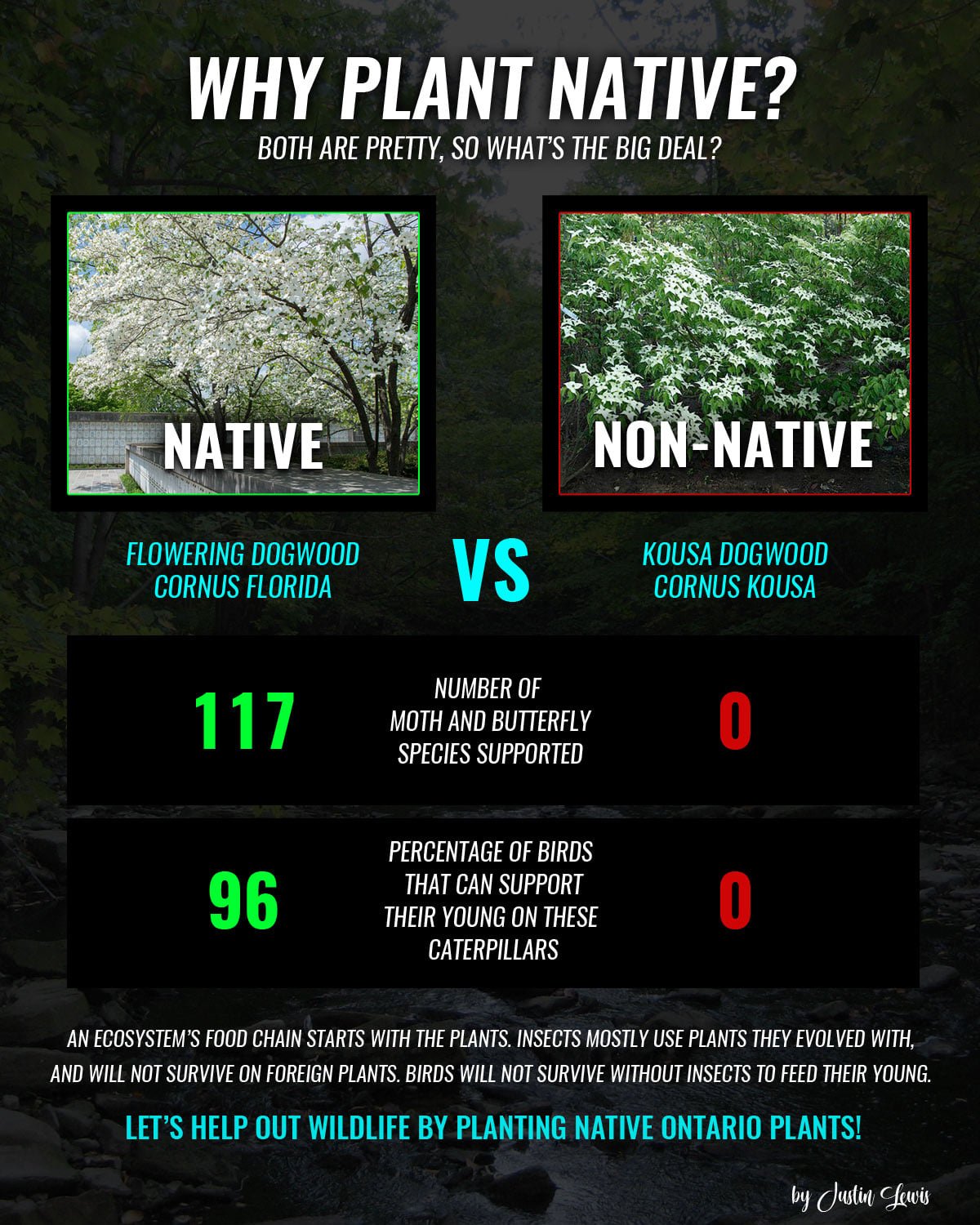

It’s important to note that the native Flowering Dogwood is not the same as the non-native Cornus Kousa, which is a popular dogwood sold at many local nurseries.

Although the two understory trees share many similarities – including large white flowers followed by red fruit – their differences are so widespread that they are really not interchangeable in the landscape.

Where they do stand out in the landscape is when you can combine them for early spring flowering in the native dogwood, through summer and late summer flowering by the non-native Cornus Kousa. The combination brings the woodland to life in an elegant display of gorgeous dogwood blooms that last almost throughout the gardening season.

• Where the native dogwood flowers in spring into early summer, the Cornus Kousa flowers pick up where the native ones begin to die out and offers flowers into late summer.

• Where native dogwood flowers grow more or less on bare branches that really show off the flowering bracts, Cornus Kousa flowers later in summer after the leaves fill out on the tree providing a beautiful showing but not quite as impressive as that offered by the native Flowering Dogood.

•Where native dogwood’s fruit is more like a drupe in clusters of 3-5, Cornus Kousa tends to put out singular fruits that look like raspberries.

• Where native dogwoods grow in a mounding, horizontal habit, Cornus Kousa tends to grow in a vase shape that eventually sends out horizontal branching if left untrimmed.

• Where the native dogwood is susceptible to disease and deer predation, Cornus Kousa, is more or less free of these problems including Anthracnose.

• Where the native dogwood is a magnet for local wildlife both as a host plant for larvae and insects through to providing an excellent food source for birds and other mammals, Cornus Kousa is neither a host plant for native caterpillars and insects, nor are its berries a great source of food for birds. Some birds and mammals (Squirrels and chipmunks) will eat the fruit but its certainly not their first choice.

• Cornus Florida supports up to 117 moths and butterflies, whereas Cornus Kousa is not known to support any in the larval stage.

• Cornus Florida also supports close to 100 birds from caterpillars that use the tree as a food source, while Cornus Kousa is not known to support any birds as a larval host.

How to water a Dogwood tree

Since the dogwood grows in a very horizontal fashion it has a very wide “drip zone.” And, because this drip zone extends out so far from the trunk of the tree, it serves little to no purpose watering the tree close to its trunk.

Look up to establish how far the tree’s branches stretch out from the main trunk and use that as your watering zone for the tree. Slow, deep waterings are necessary to keep the soil around the tree’s roots cool and moist. An all-day drip being moved around a mature tree throughout the day would be ideal during hot, dry periods with low rainfall.

Smaller, or newly planted trees would need less watering, but be sure to water deeply around the entire perimeter of the tree.

How to prune a flowering dogwood

The dogwood is a slow growing tree that tends to self prune over time. Deadwood can be cut out as it appears, but it’s important to maintain the tree’s elegant horizontal branching habit rather than try to shape it into something it does not want to be.

If grass is growing under the tree (never a great idea, better to have either living, or bark mulch), it’s best to limb up the tree as it grows and then maintain it by pruning the trees outer branches lightly to reduce the weight of the branches laden with flowers.

Try not to heavily prune the tree by taking out large branches because you will be removing the best attributes of the tree – primarily its spring flowers. It is best to just remove the smaller outer branches to reduce the weight and thus help to keep the skirt of the tree high enough to walk under.

I always prefer, if possible, to plant the tree in an area where it can take on its natural shape and not be severely pruned up.

If you are unsure how to get the most out of your dogwood, it’s probably best to hire a well-respected pruning expert to maintain the shape of these trees. Ensure the tree company is familiar with pruning ornamental trees and not just one that specializes in removing trees or large dying branches.

Bunchberry is the ideal woodland ground cover

Bunchberry or Cornus Canadensis is the perfect ground cover for the woodland garden. It is happy in a moist, acidic soil growing in a coniferous or mixed forest. The small, ground-hugging dogwood looks great in spring summer and fall complete with perfect little flowers and bunches of bright red berries.

Cornus Canadensis has a place in every woodland garden

I’m not sure when I fell in love with Dogwood, but one look at the garden in spring and there is no denying that dogwoods take centre stage in our woodland garden.

Several Flowering dogwoods (Cornus Florida), a couple of magnificent Kousa dogwoods (Cornus Kousa), and a lovely Cornus Mas or Cornelian Cherry bloom along with Redbuds and Serviceberry in a delicate display of pinks, reds and airy white-flowering trees.

There is one, however, critical dogwood species (members of the Cornaceae family) that has been missing in action in our garden and that is Bunchberry.

Bunchberry is a stunning native Woodland ground cover

Bunchberry (Cornus Canadensis) is the perfect ground cover in the moist woodland garden, whether in late spring to early summer when its attractive white bracts and greenish to purplish flowers are in full bloom against shiny green leaves, or later in summer and fall with its stark red cluster of berries and more muted purple to red leaf colour brings the woodland floor to life in a riot of colour and texture.

We know that most dogwoods are small trees or shrubs, but this plant is a low, creeping perennial that grows mostly in moist coniferous to mixed forests, clearings and boggy areas. Bunchberry can have 4 to 7 leaves, though it typically sports six in a terminal whorl with one to two leafy bracts below those leaves.

The semi-evergreen, 2-8 centimetre long leaves, like most dogwoods, have prominent parallel veins. The white flowers are, in reality, a set of four white bracts surrounding a tight pincushion of tiny greenish-white to purplish flowerlets in an umbel cluster.

Looking for more information on ground covers? Please check out my other posts on ground covers I use in the woodland garden.

• What is the easiest ground cover to grow?

• Three great ground covers for the woodland garden.

• Creeping thyme as a ground cover

• Snow in summer ideal for hot dry areas

• Moss and moss-like ground covers

When do Bunchberry flower and set fruit?

If you have never seen this often over looked native ground cover, think of the beauty of a flowering dogwood tree growing just a couple of inches off the ground in large, spreading flowering mats complete with its showy flowering bracts that bloom in late spring through early summer depending on growing conditions.

The impressive bracts and flowers are followed by bright red bunches of fruit in late summer and fall, which is where Bunchberry obviously got its name.

That’s, in essence, what the bunchberry provides gardeners. Not to mention its inherent benefits to local wildlife, including birds, mammals, butterflies, insects and bees.

Can you ask for more in a native ground cover?

For more on using Bunchberry as a groundcover, check out this Pacific Northwest landscaping plan that uses bunchberry.

In fact, according to the highly informative site Tale of the Dogwood: “The flowering shoots (of Bunchberry) often cover large areas with up to 300 flowering shoots per square meter. With an average of 22 flowers per shoot, bunchberry often has 6,600 flowers in one square meter. (10-11 square feet).”

More of my posts on Dogwoods

For more information on Dogwoods, please check out my other posts listed here:

Dogwoods: Find the perfect one for your yard

Flowering Dogwood: Queen of the Woodland garden

Cornus Kousa: Impressive non-native for the woodland garden

Pagoda Dogwood: Small native tree ideal for any garden

Cornus Mas: An elegant addition to the Woodland Garden

Why do Bunchberry flowers explode?

And if that’s not exciting enough, the flowers have been known to “explode” when a certain size insect lands on them.

Tale of the Dogwood explains that: “Exploding flowers may enhance insect pollination in two ways. First, exploding flowers limits pollinators to those insects that are heavy enough to trigger open the flowers. Large insects readily move between inflorescences whereas smaller insects (e.g., ants and small flies) are ineffective pollinators because they rarely move between inflorescences. Second, most of the large insects are voracious pollen eaters. The explosive flowering disperses the pollen over the body of the insects and imbeds it deep in their hairs where it is hard for them to gather it to eat.”

Even if a full understanding of the whole explosive nature of the flowers is of little interest, You have to admit that it’s pretty cool to have thousands of exploding flowers in your backyard!

I’m proud to say that this impressive ground cover is no longer absent in my garden. Thanks to Ontario Native Plants, I purchased a number of Bunchberry plugs late last summer and got them into the ground in time to get them started.

The plugs of this lovely woodland ground cover were planted in our shady side yard on a slight slope among the wild violets, and I am looking forward to seeing how they come through our difficult winter and begin putting down roots this growing season.

How to plant bunchberries

I planted the bunchberries in a shady area of the yard near some young pines a spruce tree and under a maple. I added a little acidifier to the planting holes and topped them with some pine needles. In spring I’ll sprinkle a little more acidifier on the soil and add more pine and spruce needles to help maintain a slightly acid growing medium.

They will be growing amid wild violets and I’m hoping to add some maindenhair ferns to complement the low-growing ground cover.

A couple years back, I tried to get three clumps of bunchberry started, but after moving them to different parts of the garden, (I must stop movng plants around every spring) the plants just disappeared. I’m not sure if they died as a result of my moving them around or improper growing conditions. Although these plants are farely common in nature, they do require specific growing conditions to be their best.

I have no plans to move these new plants, and hope that they will feel at home in the mostly shady, damp soil.

These slow-growing herbaceous perennials grow to between 10-20 cm (3-8 inches) in height as they form large clonal colonies in carpet-like mats of green leaves that, in the fall, turn a beautiful shade of red to compliment their red-tinted veins.

When does Bunchberry fruit and is it edible

Flowers appear in late spring from May through to July followed by fruit that can appear from late July into October. The berries are edible but are best left for the birds and other garden wildlife that depend on the berries to help get them through tough winters.

The drupes (fruit) start off green, turning a bright red as the clusters mature throughout the summer. Each fruit is about 5mm in diameter and contain one or two ellipsoid-ovoid shaped stones which can be planted as a method of propagation.

Where does Bunchberry grow?

Given that Bunchberry is a tough perennial ground cover found in low, almost sub- to sub-alpine areas, in most parts of Canada and the northern United States including Colorado and New Mexico all the way to Greenland, I’m confident these young plants will come through winter raring to set roots come spring.

Bunchberry’s vigour is also evident considering it’s native to Japan, North Korea, northeastern China and parts of Russia. Those countries offer pretty extreme conditions for this lovely little ground cover to call home.

Soil conditions for growing Bunchberry

They grow in poor to medium soil that can be moderately-dry to wet, but they prefer a moist, acidic soil.

Cornus canadensis likes cool, moist soils to prosper. It grows in montane and boreal coniferous forests, where it is often found growing along the margins of moist woods, preferably among cedars and on old tree stumps, in mossy areas, and among other open and moist habitats.

Try growing Bunchberry in an old tree stump

Here is an idea readers might want to trying this summer. I plan to get an old hollowed out tree stump, fill it with a rich, acidic soil and plant a bunchberry into the rotting tree stump. I’m hoping to possibly use it as a small breeding ground for additional plants that spread by rhizone.

Are Bunchberries edible or poisonous?

You may be wondering if the bright red berries of the Bunchberry are poisonous – they are not poisonous. In fact, because they are hard and a little bitter they are best left for birds and other wildlife.

The showy red, fleshy fruit turns bright red in summer and enjoyed by a host of birds and other wildlife. The seeds are mostly dispersed by birds who are often found feeding on the fruit during their fall migration. But it is also a food source for deer and moose, bears and hares as well as smaller garden wildlife species.

According to the website Adirondacks Forever Wild: Bunchberry is also used by some song and game birds. The fruits are eaten by Veeries, Ruffed Grouse, Partridge, Philadelphia and solitary Vireos, Warbling Vireos and White-throated Sparrows.”

Bunchberry flowers also attract butterflies but do not attract deer or rabbits. Deer will eat Bunchberry foliage but it is not one of their preferred food sources.

Bunchberry fruits are eaten by black bears (if they are part of your garden guests) and small mammals including chipmunks, cottontails, martens and Snowshoe Hares.

Western or Alaskan bunchberry is also a showstopper

Often mistaken for Cornus Canadensis, Cornus Unalaschkensis (western cordileran bunchberry or Alaskan bunchberry) is another stunning carpeting woodlander.

In the the informative, Gardening with Native Plants of the Pacific Northwest, authors Arthur R. Kruckeberg, and Linda Chalker-Scott describes Western buncherry as “a 6-inch-high circle of broad leaves supports a single dogwood “bloom,” a singular pattern often repeated in great swaths on the forest floor.”

They go on to explain that the “English rock gardener Reginald Farrer speaks highly of the North American species calling it much superior in showiness to the European C. suecica.”

What to plant along with the bunchberry

The authors advise that the: “dwarf dogwood should be given preeminent placing in shaded portions of the garden, under azaleas or vine maple. They like an acid, gritty soil, somewhat damp for most of the year.”

In conclusion

Woodland gardeners who are lucky enough to be able to grow dogwoods, know that you can never have enough of these important family of shrubs and understory trees. Add to this, the magnificent, carpeting qualities of the Cornus Canadensis and its western and european counterparts. These are a must for any woodland gardener.

Plant them in already-growing mats or clumps and let the rhizomes run, or get some seed and plant them in acidic damp soil to establish your own patch of this perfect, woodland ground cover.

Serviceberry: Ideal choice for attracting birds

More native plant gardeners are discovering the incredible value of the Serviceberry tree or shrub. A flush of delicate white flowers that cover the native trees and shrubs in early spring, followed by a profusion of deep red/purple berries creates a magnet for birds, bees and other wildlife. It’s the perfect understory tree for any woodland wildlife garden.

A beautiful multi-stem serviceberry in full bloom in early May. The lovely white flowers will be replace by juicy dark fruits that wildlife, especially berry-eating birds and chipmunks.

A magnet for Robins, Orioles and Cardinals

Looking for the perfect small native tree for your yard? Look no further than the Serviceberry tree.

In my garden these understory trees are a staple, together with dogwoods. My first was a single stem small tree that I planted in the front of the house close to 20 years ago. Since then I have planted several in the backyard, including multi-stem versions and a hybrid columnar form.

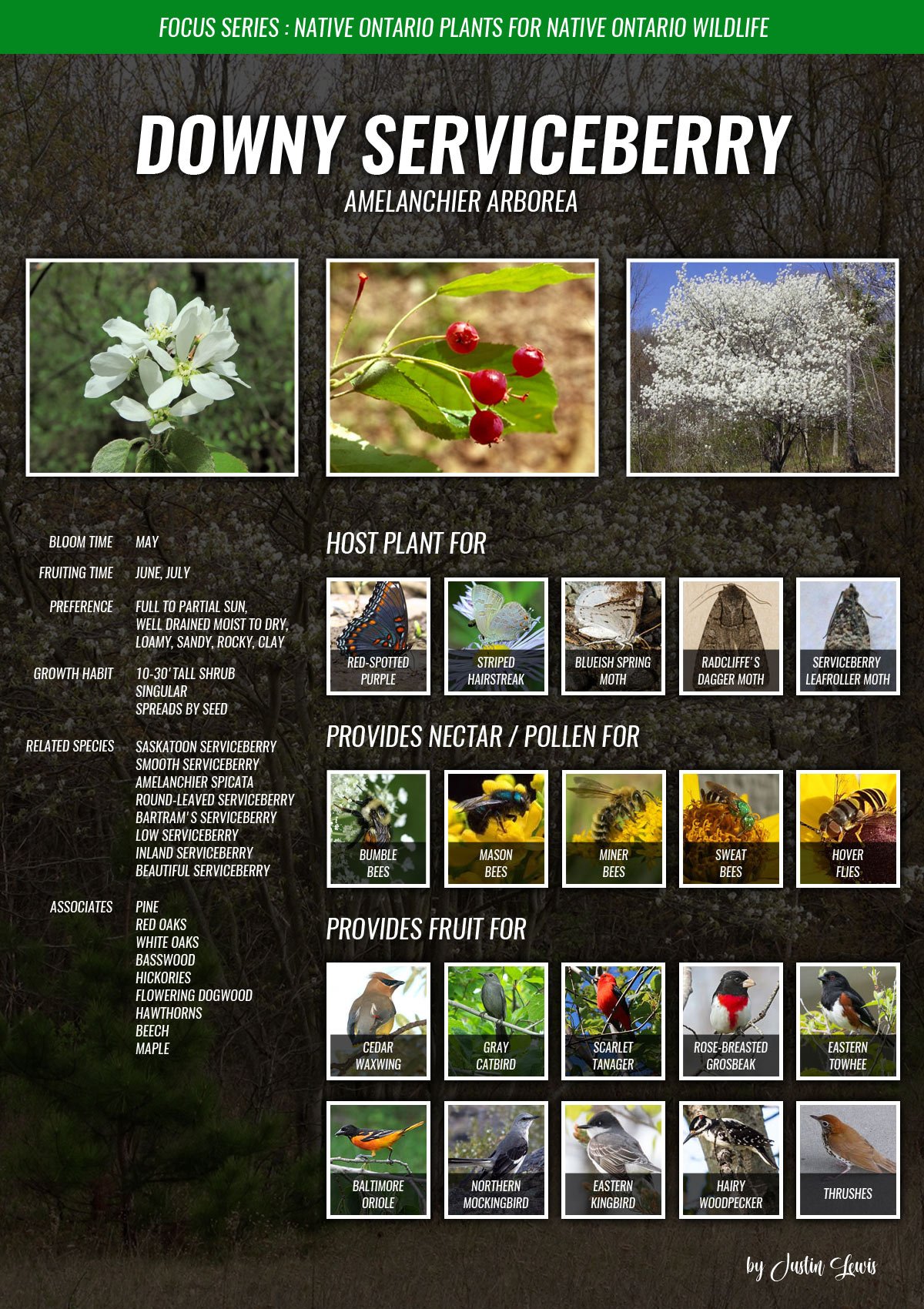

Amelanchier species can be grown as an understory tree or in shrub form and is hardy from zones 4 -9. Its delicate white sprays of flowers cover the trees in early spring (usually the first week of May where I live) and soon give way to massive amounts of juicy deep red/purple pome berries in June that are magnets to a host of birds, squirrels and chipmunks.

For my article on why native plants, shrubs and trees are important, go here.

Also known as juneberries, shad-blow, shadbush and Saskatoon berries, Amelanchier Canadensis is a member of the rose family. Both A. Canadensis and A. arborea are native to eastern North America ranging from Newfoundland west to southern Ontario and in the United States from Maine to the Carolinas.

Most of the trees and shrubs stay compact from about 6 feet in shrub form to about 25 feet tall in tree form, and are among the first to bloom in the spring woodlands providing important nectar and food sources for early emerging insects and pollinators including many native bees.

In the United States, the common serviceberry tree which is native to to the midwestern and eastern U.S. can grow to an impressive 40 feet tall in moist soil. It is a a wildlife favourite with more than 40 species of birds consuming the fruit including the cedar waxwing, eastern towhee and Baltimore oriole.

5 reasons to plant a serviceberry

• They are tough, adaptable small trees or shrubs that do well in most conditions

• Their spring flowers are among the earliest making them important native plants for early pollinators, including native bees

• Their fruit attracts a range of birds including robins, cardinals and orioles.

• They are native to Canada and the United States and an important addition to any woodland wildlife garden

• They are a host plant to butterflies and a food source for mammals

Poster created by Justin Lewis. Best viewed on tablet or desktop.

The spring bloom of the amelanchier is followed by the multitude of berries (similar to blueberries in size and flavour but sweeter) just in time to feed young birds that have fledged the nest and are looking for a good meal. Robins are often among the first to find the berries followed by orioles, thrushes, woodpeckers and cedar waxwings just to name a few.

Don’t be surprised if robins and cardinals decide to nest in the thick branches of the serviceberry.

Serviceberries trees are also important plants of the larvae of some of our favourite butterflies including tiger butterflies, viceroys and admirals.

Serviceberry flowers in full bloom from our 20-year-old tree in our front yard lights up the landscape for a few weeks in early May. The abundance of flowers will soon become berries to feed birds and other fauna.

If you garden in more remote areas, you can expect moose, deer, and other animals to browse on the leaves and twigs of the plant. The berries are also a favourite of chipmunks, squirrels and even the wily fox.

In Canada alone there are 24 species of Amelanchier that includes some varieties and some hybrids that are common in the wild. In fact Canada is a hot spot for Amelanchier diversity, potentially sporting the greatest variety in the world. Canada’s east coast boasts several including some that are quite rare (A. gaspensis and A nantuckitensis) and do not grow wild in Ontario.

The flowers of our Serviceberry in early spring. Notice that the flowers have emerged before the leaves are fully out.

The U.S. also has a few more species that are not in Ontario. All of the species share similar attributes including white flowers, gray bark and red/purple berries.

Most of these species are not grown in nurseries. In fact, most of the serviceberries seen at garden centres focus on four species – A. canadensis, A. alnifolia, A laevis and A. grandiflora.

Autumn Brilliance, a very popular nursery-grown hybrid serviceberry, is from the grandiflora species.

The many forms of wild serviceberry (Amelanchier) help illustrate their importance to native wildlife. Each flower has five long bright white petals. The flowers that bloom anywhere from March to June, depending on the species, usually grow in clusters at the end of new growth.

In Canada alone there are several forms from Amelanchier alnifolia that is native to parts of Ontario, British Columbia, Yukon and North West Territories. It grows up to three metres and can form large thickets. The flowers often precede the leaves and the fruit of this Saskatoonberry or western serviceberry is said to be the sweetest and juiciest of all the Canadian Amelanchiers.

A serviceberry in full bloom is the perfect understory tree in a woodland wildlife garden.

Amelancheir Arborea, (Link to Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower centre) also known as the Downy serviceberry or juneberry or common serviceberry is native to southern Ontario and southern Quebec where it is easily identified in spring bloom growing along forest edges and clearings often in dry soil, rocky or sandy areas. Downies grow most often as a small tree with leaves that are tapered to a point and are hairy when they are opening – which is where they pick up the name Downy.

A shrub form of the serviceberry shows off its incredible blooms that will later become a profusion of delicious berries that birds flock will likely get before you do.

Amelanchier laevis (Link to Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower centre) or often called smooth serviceberry or allegheny serviceberry are native to Western Ontario through to Newfoundland and are found in moist woodlands, clearing and roadsides.

Amelanchier stolonifera (Link to Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower centre) is a suckering shrub that grows to only about two metres tall and spreads to form thickets. It is found in the wild along sandy and rocky areas in dry woodlands, along cliffs and dunes.

Serviceberries are not picky about soil conditions and do well in sun or part-shade conditions. In the wild it is most often found growing in wet areas but, some species can be found growing in harsh areas along granite and limestone cliffs.

If all of these highlights still has not go you convinced that a serviceberry is a must for your woodland garden, consider that its fall colours are spectacular with blazing foliage in reds oranges and yellows.

Serviceberries in our garden

In our garden we are blessed with both the tree form and a small shrub that I was lucky enough to score at our annual local horticultural society sale. I planted that a few years ago, and just this year it is really putting on a nice show in the woodland garden.

Our tree form is more than 20 years old and has matured into a beautiful specimen that puts on a magnificent show every year during the first week of May. It throws the perfect light shade on the wildflower garden below and coexists nicely with a Japanese maple. Both trees have begun to merge branches forming a lovely open canopy over the native plants below, including solomon’s seal, columbine, bloodroot, wild geranium and foamflower, and non-natives that include epimedium.

Propagating from cuttings and seed

Serviceberries are easily propagated and can be rooted from early spring hardwood cutting or softwood cuttings taken during the summer months. If you want to plant them from seeds, you are going to have to collect some berries when they begin ripening and turning red to purple. Give the seeds a quick cleaning and plant them in the fall. If you plan to grow them in trays, you will have to stratify the seeds and store them in the fridge for at least three months.

More links to my articles on native plants

Why picking native wildflowers is wrong

The Mayapple: Native plant worth exploring

Three spring native wildflowers for the garden

A western source for native plants

Native plants source in Ontario

The Eastern columbine native plant for spring

Three native understory trees for Carolinian zone gardeners

Ecological gardening and native plants

Eastern White Pine is for the birds

Native viburnums are ideal to attract birds

The Carolinian Zone in Canada and the United States

Dogwoods for the woodland wildlife garden

Bringing Nature Home by Douglas Tellamy

A little Love for the Black-Eyed Susan

Native moss in our gardens

As an affiliate marketer with Amazon or other marketing companies, I earn money from qualifying purchases.

Building your Woodland: One Tree at a time

Dream of what your woodland garden can be and we will work together to make it real. By using native and non-native trees, plants and flowers, you can transform your garden into a wildlife haven. Then spend the day photographing the nature around you.

Woodland wildlife garden needs time to mature

A woodland garden can be as big or as small as you want. Start with a single tree in your yard and try to imagine what that tree can become.

Remember a woodland garden can take time to mature into perfection. Like a freshly-built home that lacks the layers living brings to it, a woodland needs that same time to develop the multiple living layers that make it the inviting place we want to experience. It too needs its spirit; one that starts deep in the soil and stretches high into the upper layers of the forest canopy. If you are just starting out developing your woodland garden design, the first rule to understand is that a woodland garden is all about layers. Three layers really, but you could argue four even six and still be correct.

It all starts with the upper canopy

The top layer, the upper-level canopy, is what builds the strength of the woodland over time. If you do it right, the middle layer is where much of the beauty resides. Then there is the shrub layer and finally the ground layer, also not without its share of beautiful things. The ground layer, appropriately made up of ground covers, forms a protective layer that encourages all that is above it to prosper.

Early morning offers a different experience in the Woodland for both photographers and dreamers. Get up early, catch the light, and sneak in an afternoon nap.

Maybe, if you are like me and bought into an older neighbourhood, you are already blessed with a mature tree or several that helps to create the critical upper canopy. If you are not blessed with any large trees on your site, that large maple growing in your neighbour’s yard casting its lovely shadow over your yard will do the trick too. Remember though, your neighbour could cut that tree down and your upper canopy can disappear in an afternoon. Better to plant your own as soon as possible as a backup to your grumpy neighbour’s tree.

This photo illustrates the layering of our mature woodland garden. A large locust and tulip tree form the upper canopy, while a mautre Cornus Kousa in full flower forms part of the mid-canopy. The kousa is joined by serviceberry, redbuds and Cornus Florida in the lower canopy of this area of the garden. Ostrich ferns fill in as the primary ground cover.

Large trees form the upper canopy

When we talk upper-level canopy, we’re talking the big boys of the tree world.

Think maples, locusts, lindens, oaks and a host of other native trees that will grow large enough to eventually tower over the garden.

If you live in the Carolinian zone (link to my post) or a similarly appropriate area and need a quick canopy, consider planting a couple of Tulip trees. They are fast-growing native trees, growing up to 35 metres tall. In fact, they are among the tallest and straightest trees in the forest. In fact, they were often the tree used as telephone poles because of their straight growth habits. Their canopy can be trimmed up high as they shoot to the sky, and the shade they throw is open enough to allow understorey plants to grow happily.

Tulip trees have a spectacular yellow-green 5 centimetre long spring blooming, tulip-shaped flowers. Although the fast-growing tree is not the best host of insects and caterpillars that provide food for birds, the seeds of the tulip tree grow every year and are a source of food for birds and small mammals.

Oaks are kings of biodiversity

If you are looking for the perfect tree to form your upper canopy, you would be hard pressed to do better than one of the mighty oaks. Consider planting an oak near your tulip trees where it will grow up to provide a future canopy after the tulip trees have served their immediate goal of providing a fast and effective canopy in the short-term.

What makes Oak trees so important?

As Douglas W. Tallamy explains in his book Bringing Nature Home: How you can sustain wildlife with Native Plants, (link to my review of the book) a single white oak tree can provide food and shelter for as many as “22 species of tiny leaf-tying and leaf-folding caterpillars.” These combined with all of the other “lepidopterans (moths and butterflies), heteropterans (true bugs), homopterans (aphids, plant hoppers,and scales), thysanopterans (thrips), orthopterans (katydids, grasshoppers, and crickets), … that develop on white oaks are considered s well, you can appreciate how important this one plant species is to the mintenance of biodiversity.

In fact, a single oak can support up to 534 different species and leads the list of important native trees providing biodiversity in our forests and woodlands.

In Tallamy’s list, The willow is second supporting 456 species followed by cherrry and plum (also 456); birch trees (413); poplar, cottonwood (368); crabapple (311), Maple, box elder (285), Elm (213); pine (203); Hickory (200); Hawthorn (159); spruce (156) …”

If attracting birds and creating a biodiversity of insects, caterpillars, moths and butterflies in your garden is important to you, I urge you to get Tallamy’s book and use it as a bible for creating your backyard landscape design.

Blessed with mature trees in our yard

When we bought our home here in southern Ontario some 25 years ago, my wife and I were blessed with several large trees on the property, including two lovely locust trees, a large linden and Austrian pine in the backyard and two large maples in the front yard of the property. Since then, more trees big and small (at last count 28) have joined the originals to help form the foundation of our woodland.

The understorey: Where the (real) fun starts

The middle layer is the one that can really shine in the woodland.

This is where you can introduce a myriad of flowering trees. Think flowering dogwoods, both the native variety (Cornus Florida) with a multiple of hybrids or the prolific Kousa Dogwoods that flower later in the season after the leaves appear on the branches. A combination of the two gives you a magnificent show from early spring into summer. Then, if you have room, intermingle a couple of Redbuds (link to my post on Redbuds) or Serviceberries between the dogwoods. Their ethereal flowers are absolute showstoppers in any garden big or small.

And, if that’s not enough, how about a couple of azaleas growing beneath the Dogwoods, Serviceberries and Redbuds. That’s a showstopper.

These are just a few ideas to think about while you contemplate your Woodland. Future posts will delve a little deeper into the different layers, so stay tuned. For example here is a post on three of my favourite groundcovers. Here is another post on a favourite groundcover for a hot dry location. This post looks into moss as a ground cover and plants that create a similar experience as moss in the garden.

I would love to hear some of your planting ideas for your top two layers your Woodlands. Share them with us below in the comment section.

This page contains affiliate links. I try to only endorse products I have either used, have complete confidence in, or have experience with the manufacturer. Thank you for your support.